The latest monthly jobs report was much better than expected, but nonetheless finds employers across the U.S. still crying out in vain for workers. Goods are undelivered for want of truckers. Code is unwritten for want of coders. Hotel beds are unmade for want of bed makers, with both Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc. and Marriott International Inc. dispensing with automatic daily housekeeping at their nonluxury properties. Even the Internal Revenue Service’s struggle to have enough people to deal with taxes on time is bordering on the apocalyptic.

The obvious reason for all of this, of course, is the coronavirus pandemic, supercharged by the omicron strain. Yet in many ways the impact of the Covid-19 crisis on the workforce, whether through workers calling in sick or choosing to drop out, merely highlights problems that were already in place or at least on the horizon. What has been eagerly dubbed the Great Resignation has hastened a demographic squeeze that was the inevitable consequence of the retirement of the baby boomers and the decline in the birthrate.

The deeper problem is that the talent model that has served America so well, especially since World War II, is breaking down. Korn Ferry, a human resources consultancy, warns that “the United States faces one of the most alarming talent crunches of any country” in its 20-country study. The institutions, practices and mind-set that enabled the U.S. to create a workforce capable of powering the world’s biggest and most dynamic economy are threatened by decay, disarray and disruption. And that is happening while China, a rival hostile power that poses an even greater challenge than the USSR once did, pulls ahead of it in world-defining technology. Once galvanized to action by the USSR’s launch of Sputnik, the U.S. now witnesses the equivalent of the launch of a dozen Sputniks from Beijing every year, with no corresponding response.

In that respect, the Covid pandemic provides both a timely warning and a spur: a warning of what happens to a historically rumbustious economy when workers become scarce, and a spur to fixing America’s long-term talent and labor-supply problems while there is still time.

The case for action is particularly urgent with top talent. After so many decades of economic and military supremacy, the U.S. has fallen into the habit of thinking that it has easy access to all the intellectual excellence it needs. The country’s great universities will always be able to find geniuses hidden in the Great Plains or the swarming cities, the thinking goes, and if, by some chance, there aren’t enough of those, then it can always raid the rest of the world. Yet today the demand for top talent in the corporate world and elsewhere is exploding just at a time when the supply is threatened, as the public school system allows exceptional talent to molder and other countries do more to retain their own exceptional performers. The country needs to add a new strand to educational reform: not just giving a helping hand to the poor or average performers but also identifying and nurturing the superstars who will help the U.S. beat back the challenge from Xi Jinping’s China.

The American Talent Economy...

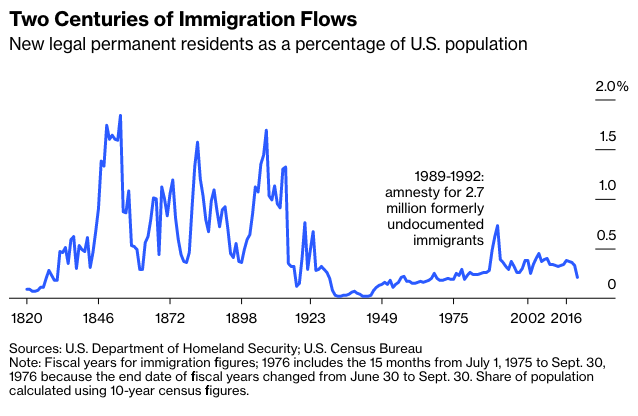

In 1958, historian David Potter published a book whose title captured the spirit of his country, at least as it appeared to the prosperous majority: “People of Plenty.” The “plenty” refers not only to the U.S.’s relative material abundance compared with other countries but also to demographic and educational abundance: America has thrived in the long term because of a generous supply of both people and skills, delivered by a combination of high fertility and immigration. In the 19th century, the population multiplied by a factor of almost 15, to 76 million from 5.3 million. By 1890, some 80% of New York’s citizens were immigrants or the children of immigrants, as were 87% of Chicago’s.

There have been exceptions to this pattern. The 1924 Immigration Act choked off immigration for decades, and the Great Depression suppressed fertility sharply. But they have not been enough to block the swelling demographic tide. The postwar baby boom sent the population soaring once again. In the 1960s, women began to enter the workforce in large numbers. In the 1970s, high immigration resumed. From the 1980s onward, a succession of presidents celebrated demographic abundance.

The U.S. led the world in three great revolutions in education—creating a mass primary school system in the 19th century, and then mass high school and university systems in the 20th. The proportion of 17-year-olds who completed high school rose from 6.4% in 1900 to 77% in 1970. The proportion of high school graduates who enrolled in universities rose from 45% in 1960 to 63% in 2000. Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz of Harvard University estimate that the mean educational attainment of the U.S. workforce increased by 0.7 years per decade over the nine decades from 1915 to 2005, and that the improvement in educational attainment contributed almost 0.5 percentage points per year to the growth of productivity and output per person.

America was in a strong position in job-related skills, particularly in comparison with the world’s former hegemonic power, Great Britain, where the educational world had an ingrained disdain for all things vocational. America’s leadership in the creation of a mass educational system stood it in good stead for the industrialization of the late 19th century and the mass-production boom of the postwar era. America also had a due respect for practical education. Legislation in 1862 and 1890 established land-grant colleges, which were focused on science, engineering and agriculture. Technology- and science-centered institutions such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology were designed to rival elite colleges such as Harvard in the practical world.

America’s advantage was particularly marked in the realm of high-level cognitive skills, thanks to its elite universities and its ability to attract intellectual stars from across the world. It pulled off the remarkable (some thought impossible) feat of creating a mass university system while also perfecting the German model of the elite research university—creating what Clark Kerr, the president of the University of California from 1957 to 1967, called a multiversity. It also turned immigration policy into a tool of intellectual supremacy. Great universities like Berkeley attracted the world’s best scholars through the sheer force of their excellence, while the federal government went out of its way to recruit scientists who could contribute to military research, even to the extent of getting its hands on former Nazi scientists after World War II.