Last week, Congress was able to push back a fast-approaching deadline for raising the debt ceiling to December. Markets applauded the move with a relief rally. Despite decreased uncertainty in the near term, we may be confronted with the same problem again in a couple of months. This week we look more closely at the role the debt ceiling plays in government financing, what could happen if the debt ceiling is not raised in a timely way and why market participants were skittish about the approaching deadline as we look ahead to December.

Democrats and Republicans struck a deal last week to raise the debt ceiling, prompting a relief rally in equity markets. While failing to raise the debt ceiling was extremely unlikely, if it had happened it could have potentially done considerable damage to markets and the economy. But even approaching the deadline when the government would no longer be able to meet its obligations was having an impact. The mere appearance of Democrats and Republicans playing politics with the deadline was weighing on markets and forcing businesses to prepare for the very unlikely, but still possible, outcome of a government default.

Unfortunately, we may have to do this all over again in December, and Congress does not yet seem to have fully learned from the 2011 debt-ceiling debacle that this issue is not to be taken lightly. Even if the current solution is just kicking the can for a couple of months, it does remove the immediate danger and opens up additional paths to address the problem well before the next deadline.

The important debt-ceiling debate will continue, although with a reduced sense of urgency in the near term. In this Weekly Market Commentary, we take a closer look at the debt ceiling and the potential consequences of failing to raise it.

13 Questions Answered About The U.S. Debt Ceiling

1. What is the debt ceiling? The debt ceiling is the limit on how much the federal government can borrow. Unlike every other democratic country (except Denmark), a limit on borrowing is set by statute in the U.S., which means Congress must raise the debt ceiling for additional borrowing to take place.

2. Why does the U.S. do it differently? The debt ceiling was originally created to make borrowing easier by unifying a sprawling process for issuing debt to help fund U.S. participation in World War I. The process was further streamlined to help fund participation in World War II, creating the debt-ceiling process in use today. According to the Constitution, Congress is responsible for authorizing debt issuance, but there are many potential mechanisms that could make the process smoother.

3. Why is it important to raise the debt ceiling? The government uses a combination of revenue, mostly through taxes, and additional borrowing to pay its current bills—including Social Security, Medicare, and military salaries—as well as the interest and principal on outstanding debt. If the debt ceiling isn’t raised, the government will not be able to meet all its current obligations and could default.

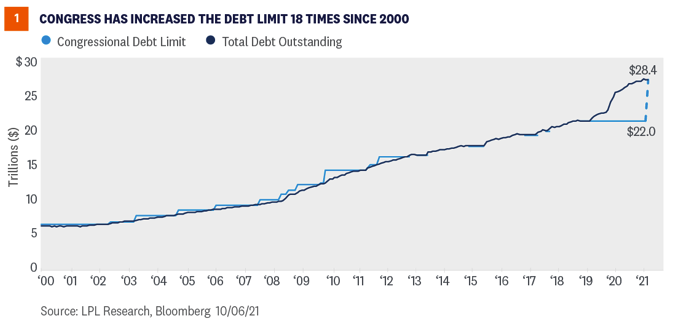

4. Has Congress always raised the debt ceiling? Yes, whenever needed. According to the Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”), since 1960 Congress has raised the debt ceiling in some form 79 times, 49 times under Republican presidents and 30 times under Democratic presidents. As shown in Figure 1, Congress has regularly raised the debt ceiling as needed. In fact, every president since Herbert Hoover has seen the debt ceiling raised during their administration.

5. Is the debt ceiling being raised to cover potential new spending programs? No. Lifting the debt ceiling does not authorize any new spending. The debt ceiling needs to be raised to meet current obligations already authorized by Congress. Theoretically, not raising the debt ceiling would limit spending in the future, but only by deeply undermining the basic ability of the government to function, including funding the military, mailing out Social Security payments, and making interest and principal payments on its current debt. While perhaps symbolic of excessive spending, the debt ceiling is not the appropriate instrument to limit spending. Spending responsibility sits with Congress and the president, but Democrats and Republicans have both favored deficit-financed spending once in power. Bill Clinton’s presidency, much of it with a Republican Congress, was the only one that saw the publicly held national debt decline since Calvin Coolidge in the 1920s.