Key Points

- Household debt relative to income has plunged since the financial crisis.

- Debt servicing is easy courtesy of low interest rates.

- But preferences have changed and households much prefer savings over debt.

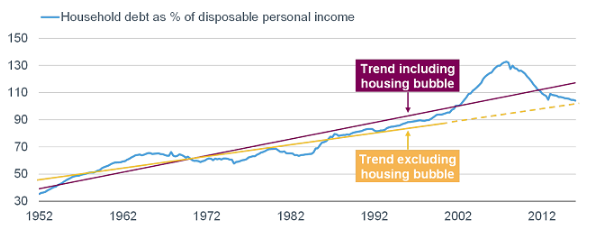

Source: FactSet, Federal Reserve, as of March 31, 2016. Purple and yellow lines represent trend lines.

Much ink has been spilled on the post-debt supercycle era in which we sit, including by yours truly. In today’s report, I want to focus on households; perhaps because the U.S. public sector hasn’t yet begun talking honestly about its debt problem. However, households were “forced” into their deleveraging cycle when the financial crisis hit following the bursting of the housing bubble.

As you can see in the chart below, the ratio of household debt to disposable income in the United States fell dramatically in the aftermath of the financial crisis. Many argue that the trajectory of debt still needs to come down, and I agree; although debt has declined to near the pre-bubble (dotted) trendline which is good.

However, as Bank Credit Analyst (BCA) opines, rightly so, debt levels are still very high by historical standards; and there is no reason to assume that the pre-crisis trend of an upward sloping debt-income ratio remained intact after 2008. The crisis could well have been the catalyst for the trend to become flat or even downward sloping. Alternatively, even if the ratio was back to trend, there could be an extended period where it falls below the trendline as a reaction to the earlier massive overshoot to the upside.

Debt growth picking up

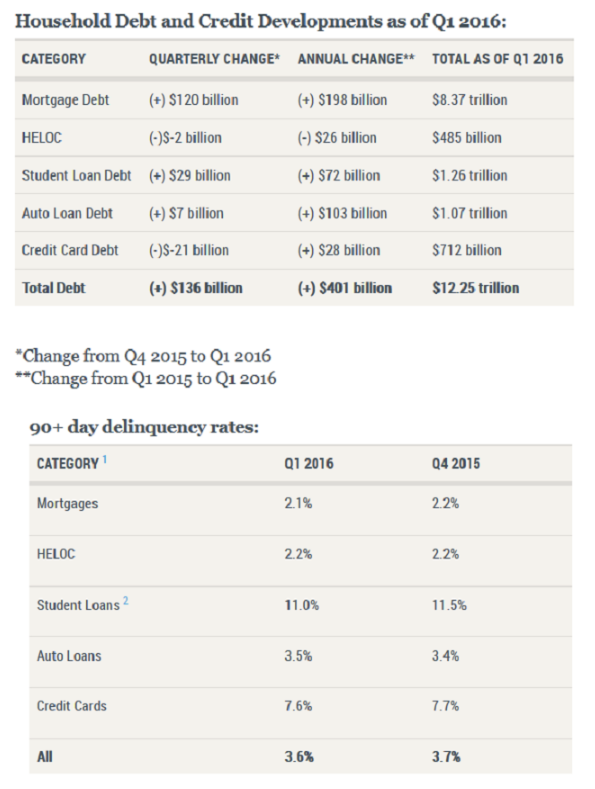

According to the New York Federal Reserve, total household debt rose a slim 1.1% in this year’s first quarter to $12.25 trillion. That’s the seventh consecutive quarterly increase; with the largest increase in mortgage debt since before the last recession began. However, households’ disposable personal income growth has been rising faster, which means the ratio of debt to income is still falling.

Not surprisingly, the increases outside of mortgages were concentrated in auto and student loans; but credit card and home equity debts declined. The best news is that credit quality has continued to improve, with newly delinquent loans rising by the least since 2005. The percentage of loans at least 90 days delinquent did increase slightly for autos, but fell for mortgages, HELOCs, credit cards and even student loans. You can see the data highlighted above in the tables below.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit (May 2016). Note 1: Delinquency rates are computed as the proportion of the total outstanding debt balance that is at least 90 days past due. Note 2: As explained in a previous report, delinquency rates for student loans are likely to understate effective delinquency rates because about half of these loans are currently in deferment, in grace periods or in forbearance and therefore temporarily not in the repayment cycle. This implies that among loans in the repayment cycle delinquency rates are roughly twice as high.