It’s exactly a month since Hamas’ terrorist attack on Israel ignited the latest war in the Middle East. And in exactly a year from now, the U.S. will elect a new president (who is almost certain to be someone who’s already served a term in the office).

In America, conversation has been swamped by a genuinely shocking poll published over the weekend by the New York Times showing that Donald Trump is well ahead and leads Joe Biden in five of six crucial swing states. It presented deep dissatisfaction with Biden’s presidency, with 71% of the respondents saying he was now too old to do the job.

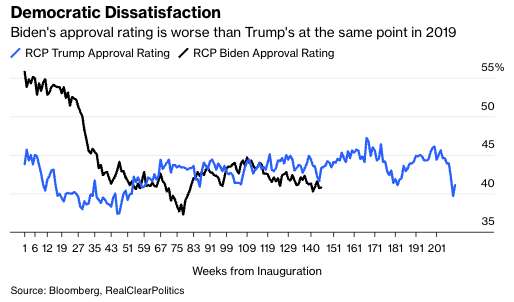

It’s important to keep this in context; regular approval-rating polls suggest that Biden is slightly behind where Trump was at the same point in his term. Trump managed to improve his popularity from there before eventually losing the 2020 election amid the pandemic:

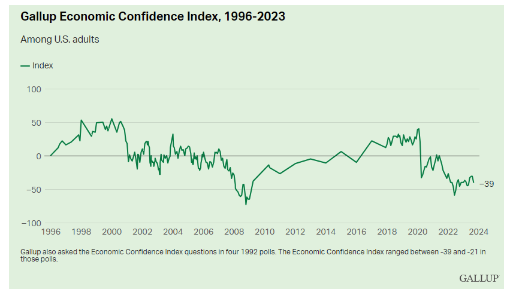

But it still makes hideous reading for Democrats, and fits with other surveys suggesting that Americans are deeply disaffected. This is Gallup’s regular poll of economic confidence, which goes back to 1996—and it can’t be good news for Biden that confidence is lower now than at the worst of the pandemic:

Internationally, the Israel-Hamas conflict intensifies and grows uglier, with ever more bloodshed and great risk of escalation in the region. It’s also roiled domestic politics throughout the west, and is showing signs of severing conventional center-left politicians from generally younger radical progressives who want full-throated support for Palestine. Most clearly, the British Labour leader Keir Starmer’s apparently effortless course to Downing Street has been buffeted by his party’s deep dissatisfaction with his support for the Jewish state. One poll shows only 9% of its supporters side with Israel in the conflict, with a huge generational division. The same trends seem to be at work in the U.S., as the crisis caused by Hamas is catalyzing just how badly younger generations have lost sympathy with Israel. So how will these political events affect the world of money?

Domestic Politics

This election is not going to be about “the economy, stupid.” The good reason for this is that the presidential candidates have made similar choices in the past, and will face similar constraints on their actions in the future:

• Fiscal expansion (as through Trump’s corporate tax cut and Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act) is ruled out by the increased deficit.

• Trump appointed and Biden reappointed Jerome Powell, a long-term governor, as chairman of the Fed. Both considered options that might have made for a more radical reset. Neither pursued those options.

• Trade policy changed sharply under Trump, but Biden has if anything intensified the economic conflict with China.

Congress is also likely to be a limiting factor, although a reelected President Trump might be given a little more room by a Republican-controlled Senate. The next administration may well have to decide how to retrench fiscally, rather than whether to do so. That could create some fascinating political debates, but the readthrough to markets is that they’re not getting another big boost from the government.

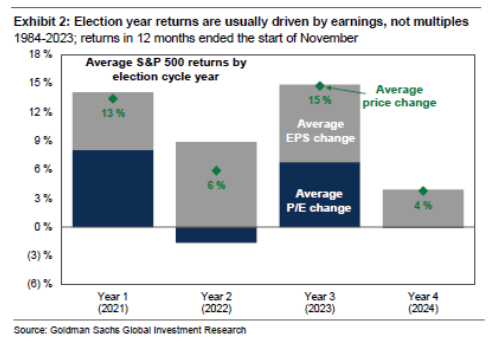

None of this means that politics or the depth of Biden’s difficulties won’t matter. Generally, presidential election years in which an incumbent is seeking reelection are pretty good for the stock market, as they’re trying to prime the pump. Since 1932, the S&P 500 has averaged a 7% return in the 12 months preceding the election compared with a 9% average return outside of election years, according to David Kostin, U.S. equity strategist of Goldman Sachs. However, when incumbents are running, the S&P 500 hasn’t declined in a presidential election year since 1952. Overall figures are also skewed by the big crashes of 2000 and 2008, which happened in election years.

Under the normal course of the presidential cycle, the third year, now approaching its end, is usually the best. Kostin shows that through all the noise, 2023 (with the S&P up 13.7% to date) has been bang in line with typical third-year performance. The final year is generally dependent on earnings growth, with political uncertainty stymieing any rise in valuations:

What might change this is monetary policy. The Fed generally doesn’t want to take actions that appear to be politically motivated. In a (perfectly believable) scenario where the economy is deteriorating severely in the summer of next year, the natural response would be steep rate cuts. That will be tough to do if it appears to be coming to Biden’s political rescue. Joe Lavorgna, chief U.S. economist at Sumitomo Nikko and a senior member of the Trump economic team while he was in office, concedes that presidents of both parties have in the past tried to put pressure on the Fed in their reelection year. His own relatively bearish prognosis for the economy would suggest that the central bank should cut rates sooner rather than later: “The politics, if anything, might argue for the Fed to do more sooner. If I’m Powell, I probably want the labor market to be weak for the next three months—because if he has to wait until the summer and then cut a lot, that would be a political problem.”

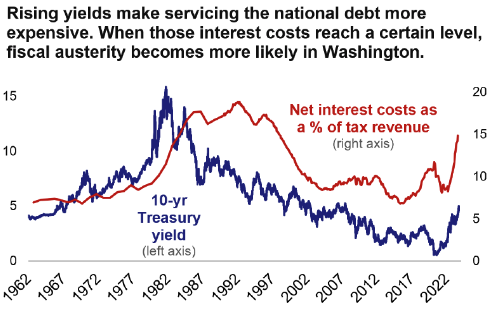

As for fiscal policy, the room for the Biden administration to do anything that would have a significant impact before the election is minimal. However, 2024 could provide an interesting taste of a new political reality in which both parties grasp that they can’t let the deficit remain unchecked. Jeannette Lowe of Strategas Research Partners predicts “more focus on offsets for new spending bills” (along the lines of Speaker Mike Johnson’s already much-ridiculed proposal to balance extra spending on aid for Israel with a cut in the enforcement budget of the Internal Revenue Service), especially as net interest costs on the national debt ramp up. She also pointed out that the total weight of the cost of servicing Uncle Sam’s debt was now almost back to its level from 1992, which led to the concerted action to reduce the deficit under President Bill Clinton:

These costs have surpassed 14% of tax revenues, historically the inflection point for a shift from fiscal accommodation to fiscal austerity. Essentially, tension is building up over how the federal government will pay for all the things that it's doing, especially if we're looking at even more spending for national security.

This chart illustrates the issue:

The big difference with the Clinton era, when deficit was turned into surplus and interest costs were halved, is that back then the Cold War had just ended and the peace dividend made it much easier to rein in the budget. That’s not the case now. On which subject…

The Middle East

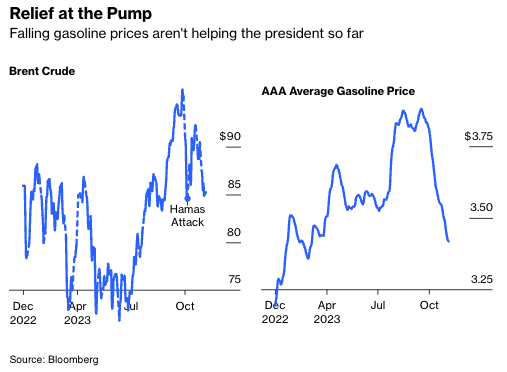

Traditionally, war in the Middle East affects everyone else in the world via the price of oil. On that basis, this conflict has had remarkably little impact up to this point. The crude oil price is barely any higher than a month ago, while in the U.S. the price of gasoline at the pump has fallen substantially (not that this has helped Biden politically):

Eric C. Robertsen, chief strategist at Standard Chartered Bank, put it this way:

To say that the market has already become numb to the risk of military escalation is probably an oversimplification. A more accurate description of market sentiment may be that the risks of escalation are now known, but investors may not position for that view without clear evidence of the conflict expanding beyond Israel and Gaza, and the market will be driven by other risk factors.

Marko Papic of The Clocktower Group, a geopolitical analyst who has always been vocally skeptical that the Gaza conflict will have broader global economic consequences, caustically commented: “Yet again, Jay Powell has proven to be more macro-relevant than Vladimir Putin, Hamas, Iran, etc. In fact, U.S. equities have actually rallied since Oct. 7, likely thanks to the abating bond selloff.”

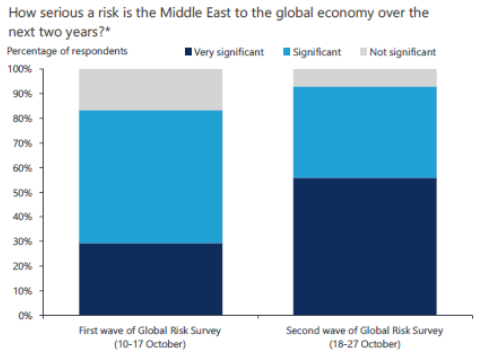

Despite this, there’s evidence that concern about Gaza in financial markets is deepening. It keeps coming up in conversations and commentaries. For example, Oxford Economics held a broad survey of large companies last month. Just in the gap between the second and third weeks of October, the proportion believing the conflict would be very significant over the next two years almost doubled:

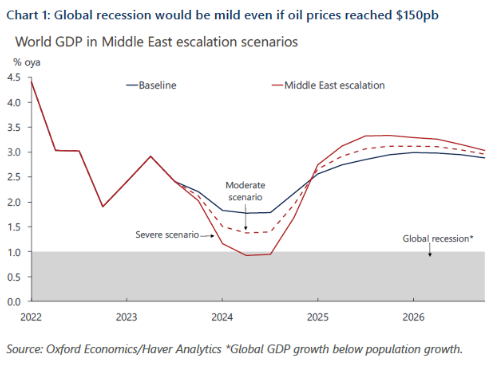

That said, Oxford Economics’ own calculations suggest even the gloomiest prognoses, involving direct conflict with Iran and enough interruption to global oil supplies to push crude above $150 per barrel, would still only just push the global economy into a recession:

Jamie Thompson of Oxford Economics said that respondents were concerned more about increasing de-globalization and the continued division of the world into different economic blocs than by specific risks of war spreading from Gaza. The conflict in Ukraine, and concerns over Taiwan, have also contributed to a growing sense that geopolitical discord will damage business.

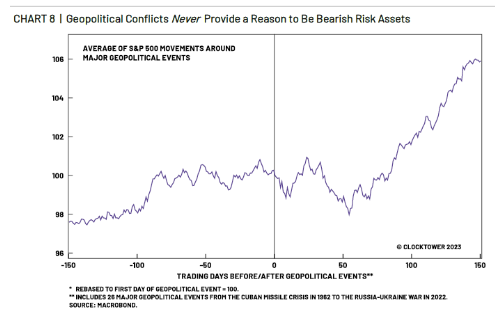

Papic believes that Israel might choose to expand the conflict into neighboring Lebanon and Syria, but “such an incursion would not have global market relevance.” He added: “The only global macro risk—an Israeli unilateral attack against Iran—is unlikely given extreme U.S. opposition.” Attacks by national armies against Israel he considers highly unlikely. He also offers this spectacular chart to show that big geopolitical events don’t have big market impacts, at least in the first months after they happen:

Taking the exact opposite tack is Matthew Gertken of BCA Research, who warns against market complacency. His argument is centered on the U.S., for whom he says the bar for military action is low, and on Iran:

The war will escalate further due to the US need to defend its credibility. President Joe Biden and senior U.S. military and national security officials have warned explicitly and repeatedly that foreign actors should not seek to take advantage of Israel while it responds to Hamas and invades the Gaza Strip. As Israel commits further to this invasion, its enemies are showing signs of intervening, which would then trigger American protection of Israel.

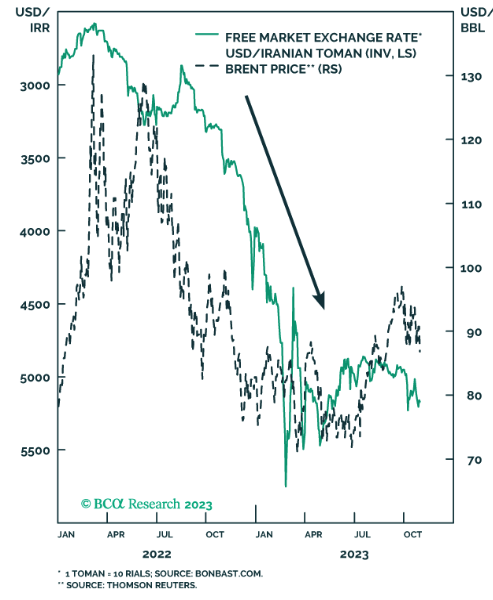

Meanwhile, he argues that Iran has an incentive to get involved, despite the extreme diffiulties of any direct attack on Israel, because it is approaching a generational change in leadership, and needs a distraction from what he describes as an economic mess. The Iranian currency has been under extreme stress:

That suggests to Gertken that the calm market response has provided an extended opportunity to buy haven assets, such as bonds and U.S. equities, while there is still time.

A final reason for caution is the simple deadening impact that political uncertainty has on investment decisions, by corporations as much as financial investors. Jean Ergas of Tigress Financial points out that risk and hazard bring with them a reluctance to invest: “You can forget the Keynesian multiplier; people stand back.” With risks elevated, he adds, the Lloyd’s insurance market in London can become an even more important player than JPMorgan; if insurers aren’t prepared to underwrite tankers or trade shipments, the situation swiftly becomes dangerous for the economy. While the conflict in Israel dominates international attention, and the risk of escalation continues, it’s as well to be careful.

Survival Tips

I went to La Bohème at the Met at the weekend. It’s the first time I’ve seen it in decades, and I enjoyed the romance of it (and the spectacle of the Zeffirelli production) far more than when I was younger. So here’s the great romantic tenor aria from the first act, sung by Rodolfo to Mimi, whom he has only just met. This is Mimi’s reply. And this is how Rent, the musical it inspired, begins in 1980s downtown Manhattan.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former chief markets commentator at the Financial Times, he is author of The Fearful Rise of Markets.