Covid-19 is truly the mother of all crises, and no economy in the world has been spared. While some are returning to growth, many are finding it extremely difficult to engineer a recovery. Advanced economies had the fiscal space to support themselves by accruing large sums of debt, but many developing economies lack sufficient financial resources to improve public and economic health. Entire nations are finding themselves on the downward leg of the K-shaped recovery, and may require forbearance from their creditors.

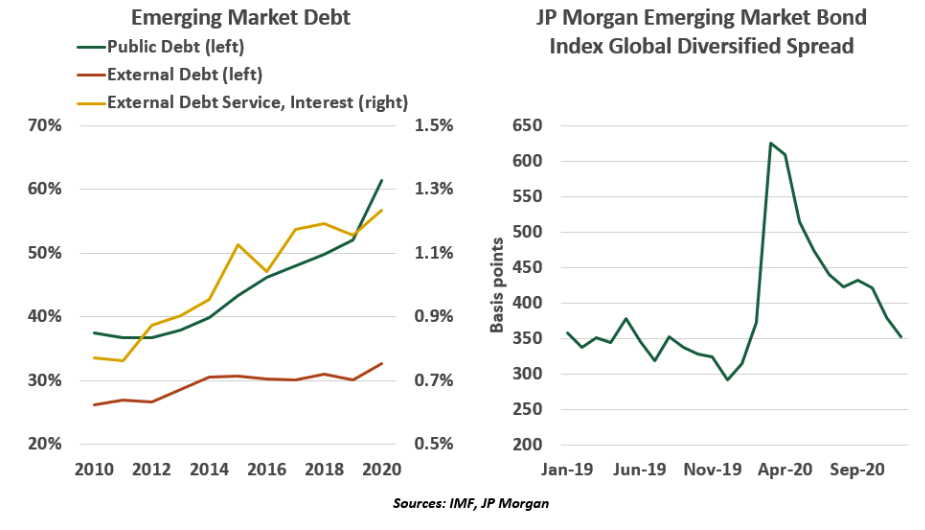

The pandemic is pushing an increasing number of developing countries into debt distress. Many of them were already experiencing what is known as a debt super-cycle, in which the interest on accumulated debt reaches to a point where it becomes difficult to service. For some countries, a crisis looks imminent, while for others the day of reckoning has been delayed by the exceptionally low global interest rate environment.

The past decade has witnessed the largest and fastest debt buildup ever seen in emerging markets (EMs). Although China accounts for a significant part of this increase, debt buildup has been broad-based across EMs. Fortunately for now, investor appetite for EM debt has been rising, pushing yields down noticeably.

With trade, tourism, remittances and investment flows disrupted by the pandemic, many EMs have seen a drastic decline in their foreign exchange incomes, which makes it harder to service their debt obligations. Problems are seen across regions; some nations find themselves back in trouble after a long history of defaults.

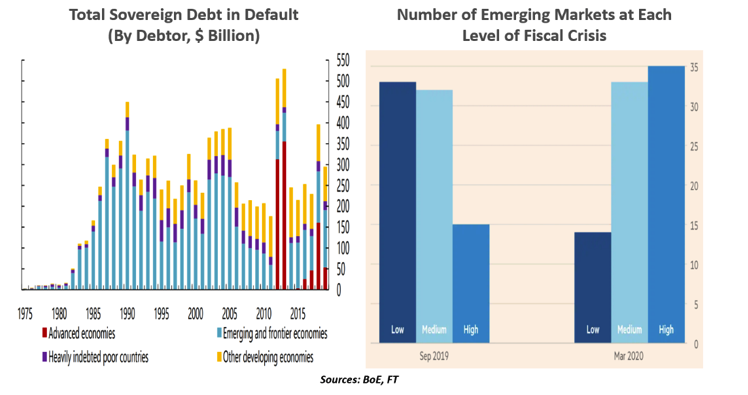

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, developing economies are facing repayments of between $2.6 trillion and $3.4 trillion on their public external debt in 2020 and 2021. Default risk is rising, and so is the call for debt relief. EMs will require support in the form of grants, concessional financing or debt restructuring.

Multilateral institutions like the Paris Club have been working on providing relief. The Paris Club is an informal group of creditor countries (usually represented by officials from Treasury Departments) focused on designing coordinated and sustainable debt relief to debtor nations. Its workload now includes 471 agreements with 99 debtor countries covering $589 billion.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is another important agent in this area. The IMF has pools of funding amassed from its members that can be used for debt restructuring: the Fund has lent $105 billion to 85 nations since March 2020 and cancelled repayments from the weakest economies. The World Bank has set aside $160 billion to lend over the next 15 months, with an additional $80 billion allocated by other development banks. These efforts, while helpful, will likely fall short of the ultimate need.

The sovereign debt restructuring process can be protracted and difficult. It involves substantial bargaining in which the debtor agrees to higher future debt in exchange for lower payments now, deferring but not eliminating default risk. As a result, a number of restructurings involve litigation by bondholders seeking to extract a preferential recovery. On average, it takes about seven years to resolve the most difficult situations, and the process typically involves multiple steps.

Several developing economies have been taking on debt on less concessional terms from private lenders and non-Paris Club members. Defaults involving the Paris Club of official creditors are declining while those involving bilateral creditors, including China, have been growing.