It helps to be prepared for medical emergencies. As the coronavirus spreads, health officials are scurrying to ensure medical facilities have adequate supplies to deal with the rising caseload.

As the economic consequences of the coronavirus spread, policymakers are struggling to formulate their reactions. Unless they improve their preparedness, it could mean the end of the global expansion.

Central banks have done their part. This week, the Bank of England surprised with a half-point rate cut, and announced a funds-for-lending program targeting small businesses. The European Central Bank (ECB) chipped in by expanding its quantitative easing program. The U.S. Federal Reserve injected $1.5 trillion of liquidity into the financial system to keep order, and is likely to reduce interest rates further at its meeting next week (if not before).

Monetary measures can help support financial conditions and bolster flagging market sentiment. But they are not the best tools for the task at hand. The lag time between central bank action and economic reaction means that recent movements may not reach their maximum benefit until after viral contagion and the related supply chain disruptions have eased.

On Thursday, ECB President Christine Lagarde called for “an ambitious and coordinated fiscal policy response” to address the spreading malaise. Her comments were primarily aimed at Berlin and Washington. Properly structured and sized, additional spending can add immediate impetus to economic activity and target it to the areas of greatest need.

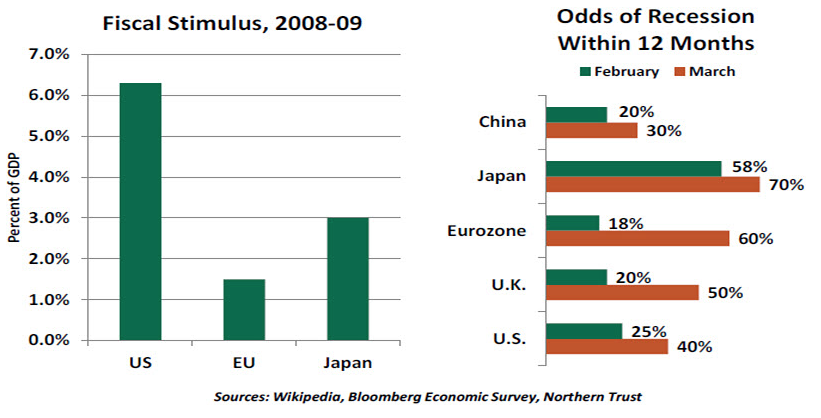

The substantial fiscal programs of late 2008 and 2009 helped hasten economic recovery and launch the long bull market that ended this week.

Fiscal policy takes more time to formulate, given more complex governance (and significantly more complex politics) surrounding the process. A range of economic actors and sectors will ask for relief, and debate will center on whether to stimulate demand with direct government spending, tax reductions, or checks to households.

Not surprisingly, China has moved most forcefully. In response to the virus, it has implemented a range of measures to support activity and minimize financial distress. The scale of its reaction matched the scale of the challenge, and there are signs of recovery in Chinese activity. While there may be costs to pay later, those costs would likely pale in comparison to allowing the economy to decline further.

Western governments have been nowhere near as quick or as bold. A few billion dollars, euros, and pounds have been appropriated to assist, but the amounts are a drop in the bucket for economies that are trillions of dollars in size. The United States has authorized only $8 billion thus far, a paltry sum compared to the $900 billion of fiscal stimulus passed in 2008 and 2009. Cautious measures fall well short of the “shock and awe” that will be needed to arrest any declines in consumer, business and market confidence.

The American response to the spreading crisis has been entirely insufficient. The process has been hindered by a delayed recognition of the scale of the challenge, which led to delays in the design of appropriate responses. It isn’t surprising that the White House and Congress began on somewhat different tracks, but the magnitude of the occasion should prompt much more rapid coalescence. Markets have been anxiously awaiting a resolution.