It may seem counterintuitive to suggest that today’s high interest rates will fuel shelter inflation down the road. After all, the Federal Reserve has tightened monetary policy to stamp out price pressures in the economy.

When it comes to housing though, building more is the only way to structurally address the primary driver of elevated shelter costs, and that’s going to take lower interest rates, not higher-for-longer borrowing costs.

If there was ever a time to demonstrate that more construction is a surefire way to limit increases in home prices and rent, now would be it. Coming out of the pandemic-induced recession, 2021 and the first half of 2022 offered a generational opportunity to build given where interest rates, rent growth and asset valuations were. Some metros saw a surge of new projects and now have very little housing inflation, while others missed their chance and continue to see upward pressure on home prices and rents.

In the apartment market, both government and private sector data show that rents are stable or falling in the southern and western markets where supply growth has been the most robust over the past few years. In the northeast and mid-west, where construction activity was more muted, rent growth has been the strongest.

In the single-family rental market, the fastest rent growth is currently in mid-sized undersupplied metros in the southeast such as Chattanooga and Knoxville in Tennessee, and Savannah, Georgia, according to John Burns Research & Consulting. Larger Sun Belt metros that built a lot more housing including Austin, Phoenix and Las Vegas have essentially no rental inflation at the moment.

Overall, the stickiness of shelter inflation has surprised many people, including me. But the lack of supply in some regions and high mortgage rates have combined insidiously to keep homes expensive, pressuring rents higher as potential buyers find themselves stuck in the rental market since they can’t afford to buy.

Perversely, elevated shelter inflation is a major factor leading the Fed to hold rates higher for longer, hindering construction.

This is most obvious in the apartment market, where data last week showed multi-family housing starts fell in March to the weakest level since the pandemic lows. I wrote a couple of weeks ago about how fewer new apartment projects now will constrain supply and push up rent growth as soon as 2026. With hotter-than-hoped-for inflation readings delaying policy easing beyond the summer, this scenario is looking even more likely.

And even though the data for housing starts in the single-family market looks somewhat better, at least relative to the low construction levels of the 2010s, high borrowing costs are creating challenges there as well. In response to a question about building for single-family rental operators, Ryan Marshall, CEO of PulteGroup Inc., said on Tuesday that “the interest rate environment currently ... makes it harder for the single-family rental operators to underwrite their deals.”

Financing costs have also contributed to market share shifts within the homebuilding industry, with implications for the pace of construction in different parts of the country.

The big publicly traded homebuilders such as DR Horton Inc. and Lennar Corp. can finance new projects via their own cash flow or the capital markets, helping them gain market share largely at the expense of privately held homebuilders, who need to borrow from banks. Metro areas where the largest homebuilders don’t operate—for instance those in the northeast—will find it increasingly difficult to build their way out of their housing shortages unless borrowing costs moderate.

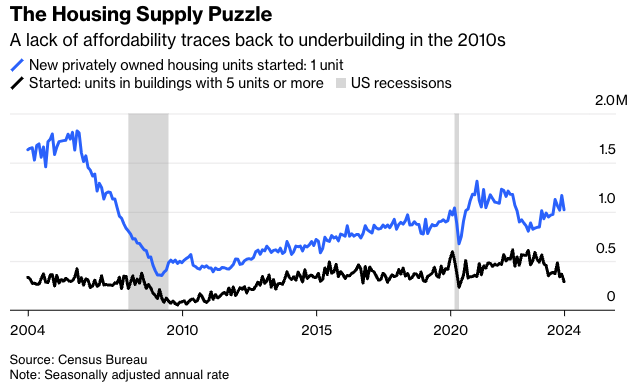

Arguably the root cause of America’s broad-based shelter inflation problem is the underbuilding that occurred following the 2008 recession, which only caught up to us when demand for housing surged during the pandemic. Notably, government measures of shelter inflation were low in the early 2010s when the underbuilding was happening, a reminder of the lags between supply, demand and inflation when it comes to housing.

The central bank is aware of these dynamics. On Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast last week, Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin said, “the theory of the case is that you raise rates, it brings down demand to levels more in balance with supply...you get inflation under control and then you can lower rates again so that supply can blossom.”

But that’s more a best-case scenario than a base case. Even though many private sector measures of shelter inflation show lower numbers than the government data, which is running around 5%, it’s possible the government measure stays elevated or price pressures in other parts of the economy force the Fed to keep rates high, stifling any blossoming.

With the labor market in good shape and large numbers of millennials still “under-housed,” shelter inflation could stay warmer than the Fed would prefer for years, with central bank policy itself part of the problem.

Conor Sen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is founder of Peachtree Creek Investments.