Key Points

• Many investors pay too little attention to investment returns on an after-tax basis.

• Active tax management strategies can boost post-tax returns by 1 percent annualized.

• Passive indexes are less tax-efficient than many investors realize, but active tax-loss harvesting can enhance returns of an index-tracking portfolio, and adding a multi-factor investment strategy can further add to returns.

With the April 17 income tax deadline looming, I thought this would be an opportune time to write about our thinking on taxes and investing, along with some tax-managed investment strategies that we deploy at Gerstein Fisher. The fact that markets abruptly turned volatile from early February 2018 and entered correction (-10 percent) territory does not change the fact that many investors will be stunned to learn just how much of their bumper gains from the 2017 bull market they will need to surrender to the coffers of Uncle Sam and state tax authorities. It doesn’t have to be this way: In our experience, a successful “tax alpha” (additional return generated through active tax management) strategy can boost after-tax returns of an equity portfolio by one percentage point.

Taxes Are A Drag

To the extent that they do pay attention to taxes, many investors (and their advisors) use portfolio turnover as a proxy for tax efficiency. To us, this is a simplistic view, which blurs “bad” turnover (e.g., selling positions that trigger short-term capital gains taxes) and “good” turnover (e.g., realizing capital losses or deferring gains to the much lower long-term rate). An investor (or portfolio manager) who doesn’t focus on the tax effects of trading activity is, to our mind, passive with respect to tax management.

Before discussing the two quantitative strategies we use to enhance after-tax returns, I want to provide an example of an index fund and taxes. Many investors perceive index funds as an inherently tax-efficient solution, but in fact these passively managed portfolios are far from immune to the negative impact of taxes on investors’ bottom-line (i.e., after-tax) results, particularly when taking the relentless math of long-term compounding into account. After all, tax liabilities are generated in an index fund through dividend income, periodic index reconstitutions, and corporate events

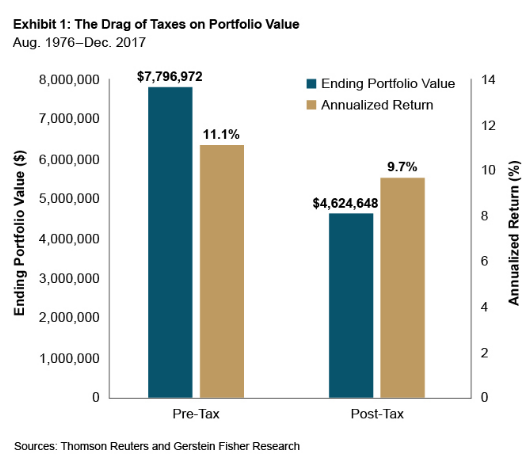

Exhibit 1 shows the effect, over 41 years, of the tax drag on a taxable investor vs. a tax-free investor holding an S&P 500 Index fund. Both invest $100,000, but the taxed investor ends up with $3.2 million less money, in effect coughing up more than 40 percent of investment gains to taxes. (Based on estimated tax rates and after-tax costs/benefits of: 40 percent for ordinary dividends, 40 percent for short-term realized capital gains, 25 percent for qualified dividends, and 20 percent for long-term capital gains. Note that these rates approximate the effective marginal tax rates for a typical investor in a Gerstein Fisher tax-managed equity strategy.) This scenario is simplified, but it demonstrates how taxes, when unmanaged, can substantially corrode a portfolio’s value over an extended time frame.