Last week, we discussed whether stock prices might be reflecting peak optimism. In that commentary, we noted that while sentiment may be overly optimistic and a pickup in volatility would be totally normal, strong breadth measures suggest stocks still may have more upside. This week, we tackle that same topic of peak optimism, but by looking at some valuation metrics. While valuations are elevated, they still appear reasonable when factoring in interest rates and inflation.

Valuations Appear Elevated On Traditional Metrics

Based on the most commonly used valuation metrics such as the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E), stock market valuations are elevated. This is hardly a controversial statement when considering the S&P 500 Index is trading at a P/E of 22 times the consensus earnings estimate for the next 12 months (source: FactSet). Even against the 2022 consensus earnings estimate, which may be a better measure given the strong earnings growth anticipated this year and next, the P/E of 20 is still several points above the long-term average of 17 since 1980. By that measure, we would say a lot of good news is priced in.

Valuations Look Quite Reasonable When Factoring In Rates

But we shouldn’t evaluate stock valuations in a vacuum. Going back to your Finance 101 days, the fundamental value of a stock is the present value of its future cash flows. When we discount future cash flows—a similar but purer measure of profits—interest rates come into play. That means we want to incorporate interest rate levels into our evaluation of P/E ratios. History shows higher interest rates have translated into lower stock valuations—and lower rates, our current situation, justify higher valuations.

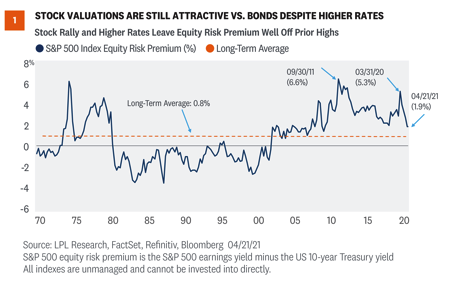

To get this fuller picture, we calculate what’s called an equity risk premium, or ERP. This statistic compares the earnings yield on the S&P 500 (the inverse of the P/E) to the 10-year US Treasury yield. Essentially, an ERP compares the earnings generated by stocks to the income generated by bonds (in this case, the yield on the 10-year Treasury). By putting stocks and bonds in the same terms, they can be compared on an apples-to-apples basis.

As of April 21, 2021, the ERP for the S&P 500 Index was 1.9%, which is above the long-term average of 0.8% but well below the post-pandemic peak of 5.3% on March 31, 2020 [Figure 1]. (Higher values mean stocks are less expensive relative to bonds, and vice versa.) Using the earnings estimate for the next 12 months rather than the last 12 months pushes the ERP up to an even more compelling 3%. So, while we acknowledge stock valuations are elevated, compared to still-low interest rates they are quite reasonable.

Inflation Is Also A Factor

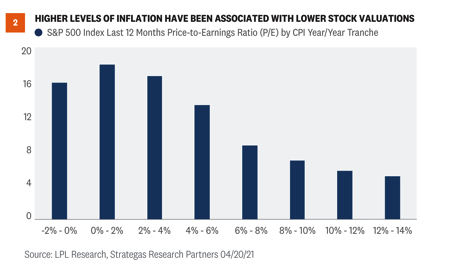

Stock valuations have also been impacted by inflation levels historically. This makes sense because higher inflation tends to bring higher interest rates along with it. In essence, higher inflation reduces the value of future profits and cash flows, and therefore leads to investors paying less for those profits and cash flows in the form of lower valuations. This relationship is shown in [Figure 2], where you can see that low inflation (2% or less, based on the consumer price index, or CPI) has historically coincided with the highest P/Es.

While we expect inflation to move above 2% due to stronger economic growth, tightening labor markets, and the base effects associated with depressed price readings early in the pandemic, valuations have historically been above average in the 2% to 4% inflation tranche, which eases our concern. In addition, we would expect higher inflation to be temporary. So, after the pandemic is further in the rear view mirror and the readings normalize, valuations may garner some support. We discussed why higher inflation may be transitory here.