In a free-market economy everyone is supposed to have the chance to get rich. The dream of making it big motivates people to take risks, start businesses, stay in school and work hard. Unfortunately, in the U.S., that dream seems to be dying.

There are still plenty of rich people in the U.S., and their wealth is increasing. But people outside that top echelon are having a tougher time breaking in. A 2017 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland found that the probability that a household outside the top 10% made it into the highest tier within 10 years was twice as high during 1984-1994 as it was during 2003-2013.

There surely are many reasons for this trend, but one of them probably is the winner-take-all structure of the U.S. economy, where a few people get fabulously lucky with their hedge fund or tech startup, while most people fail.

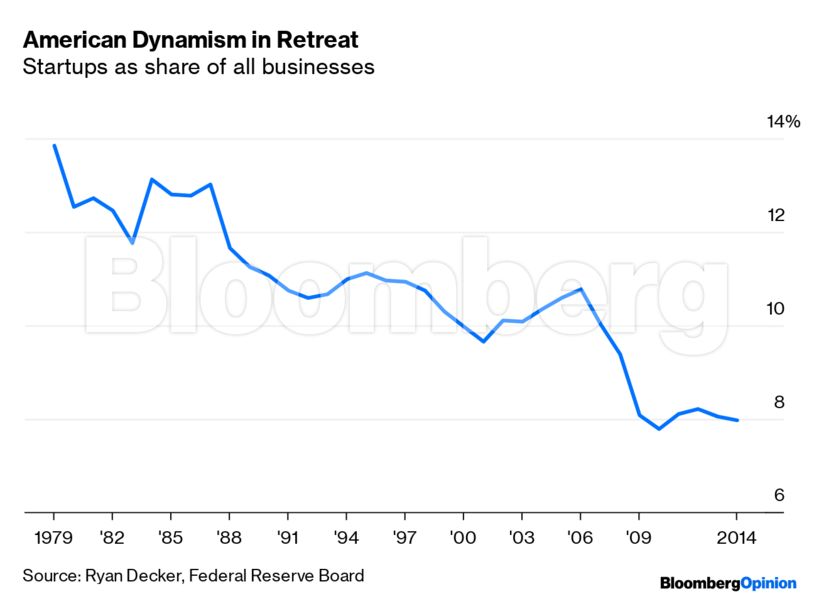

The traditional way to get rich in America is to start a business. For those of modest means, perhaps this would be a corner store or a restaurant; for the more ambitious, a technology startup. Many Americans still do this, but the number is dropping as business formation dries up:

Much of the decline is due to efficient national retail chains muscling out small local businesses. But high-growth startups are on the wane as well, and the dominance of a few giant tech companies may be making it harder for upstarts to reach the loftiest heights of success.

If you don’t start your own business, you can always invest in someone else’s. Investors who put their money into winning stocks like Coca-Cola Co. or Amazon.com Inc. made fortunes. But turning a small amount of money into a large amount in the market requires making big -- and remarkably lucky -- bets on individual stocks. Most people who try to do this end up failing. For the average American, the market is a bewildering game, full of high-frequency traders and savvy hedge funds waiting to take their money; decades of painful experience have taught individual investors that day trading is a losing bet. Most simply turn over their money to institutions, accepting the more modest but less risky returns they offer.

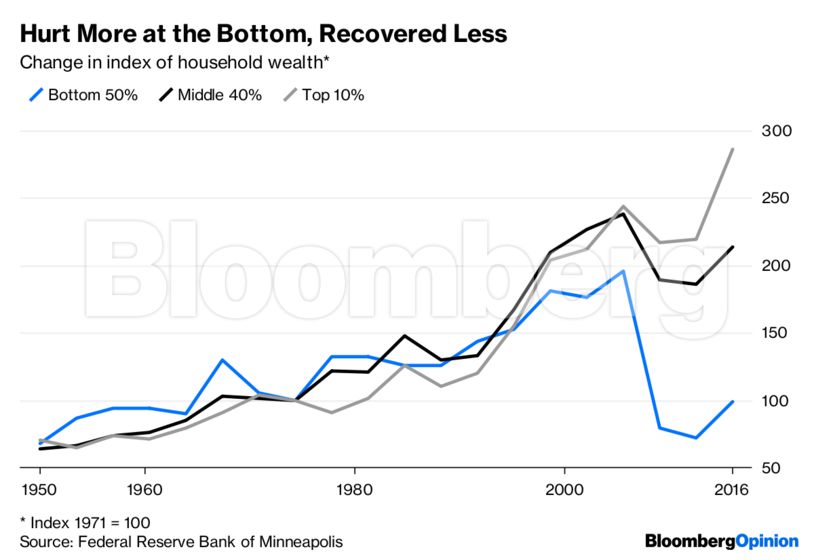

Middle-class Americans tend to have most of their wealth in houses. For the average person, real estate is a comprehensible game, where assets are tangible and visible, and market transactions often are done face-to-face. From the 1980s through the early 2000s, many Americans tried to get rich by buying and selling second and third homes. But the housing bubble, which largely was driven by this sort of activity, crushed the real estate dream for many. Others who bought only one home saw it plunge in value in the crash; those that were forced to sell their houses, usually to better-heeled buyers, were unable to recoup their losses when prices eventually recovered.

After the recession, lending standards tightened, making it harder for people of modest means to get in on the real-estate market and start building wealth. House flipping has returned, but homeownership rates have fallen, suggesting that one of the main paths to accumulating assets is no longer readily available to those of lesser means. For the middle rungs of the distribution, wealth -- most of which is in housing -- has barely recovered from the devastation of the late 2000s:

Even if one doesn’t win big in the housing or stock markets, it is possible to get moderately wealthy by working one’s way up the corporate ladder. And companies are still throwing big salaries at data scientists with doctorates, as well as executives and top managers. But hopping on the bottom rungs of the ladder usually requires an elite and very costly education. Sometimes this even means an advanced degree. That kind of credential can only be attained by way of not just talent, but increasingly a privileged background. Stories like that of former Salomon Brothers Vice Chairman Lewis Ranieri, who started off working in the mail room and ended up as the inventor of mortgage-backed bonds, are probably getting rarer.

Plenty of Americans are still starting successful businesses, picking winning stocks, flipping houses for handsome profits and polishing their resumes for top employers. But those paths to wealth have gotten narrower, more difficult and less certain. With the rise of big companies, institutional investors, tight lending standards and degree requirements, an American’s chances of making a fortune without either being a genius or having wealthy parents look slimmer than ever. It’s small wonder that so many have flocked to the world of cryptocurrency, where outsiders and people with less formal education still have a chance to strike it rich. Even there, though, institutional investors are slowly taking over.