But it’s popular to expect a return to normality, and that would include a world in which economic expansions are accompanied by rising prices. Larry Hatheway and Alexander Friedman of Jackson Hole Economics, put the risks as follows. It is worth quoting them at length:

History suggests that inflation is typically slow to emerge. But when it does, it manifests inertia, as rising prices reinforce expectations of more to come. That’s why the Fed’s overshooting objective is risky. Once inflation exceeds thresholds, bringing it down could be difficult.

Which brings us… to the implications for asset prices. Rising inflation always undermines bond returns, with their fixed nominal coupons. But bond markets are much more vulnerable today, given significant over-valuation caused by central bank asset purchases and in the context of massive future supply due to unprecedented fiscal deficits. Bond markets will be in for a rude awakening if inflation accelerates.

Some argue that equities can withstand inflation because earnings and dividends rise with inflation. That’s simplistic and dangerous thinking.

As interest rates rise, so does the rate at which future earnings are discounted. Even more important, rising inflation increases economic risk. Central banks will eventually have to dampen spending to curb inflation. Accordingly, when inflation picks up investors require a higher risk premium to hold equities. Inflation de-rates valuations, which in some cases are already very high.

In sum, investors should care about rising inflation, which is now more probable than at any time in the past two decades. When it comes, it will be fast. Given that the consequences are huge for all investors, it is time to take notice.

ECB vs Covid

Thursday will see a dose of preordained excitement as the European Central Bank holds its last scheduled monetary policy meeting for the year. Christine Lagarde, its president, already promised that the bank will “recalibrate” its asset purchases at this meeting to deal with the developing challenges posed by the pandemic, so the only (very interesting) question is exactly what the ECB chooses to do.

The latest piece of high-frequency data is the ZEW survey of German industry, conducted early this month. This suggested that the current “lighter” lockdown is having the effects that might be predicted. Expectations for the future have improved slightly and are back close to their highs for the decade. The effect of rebounding Chinese demand for German autos, in particular, should be a boon. But the assessment of the current environment remains dreadful. The central bank will plainly want to do something to tide the euro zone through this period:

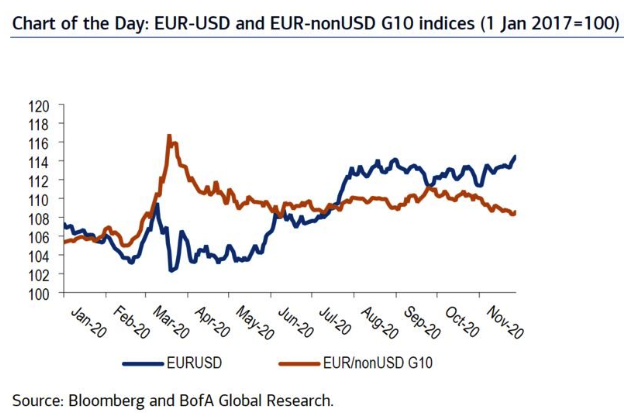

Whether Lagarde will also use this as an opportunity to push down the euro is another question. A weaker currency might help, but as the following chart from BofA Securities Inc. makes clear, the euro’s recent apparent strength is a function of the dollar’s feebleness. Against the rest of the G10 currencies, the euro spiked during the Covid shock, and is now sliding:

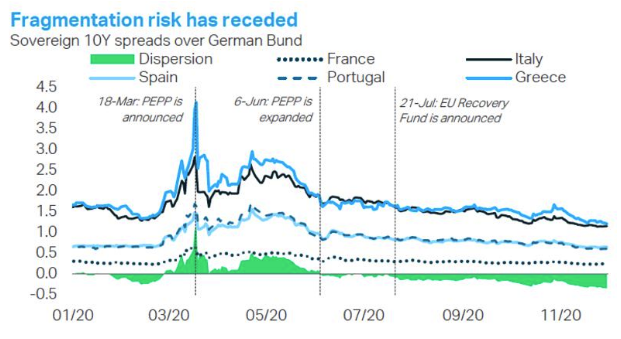

Lagarde also has a tricky political task on her hands. There has been great excitement this year over the EU Recovery Fund, in which leaders agreed after a marathon summit to borrow together to raise funds for Covid relief. There were distinct echoes of Alexander Hamilton’s masterstroke of collectivizing the states’ war debt and establishing the Treasury market, a critical step in moving the U.S. in a federal direction, and so this was hailed as a Hamilton moment. But as this chart from TS Lombard makes clear, the critical steps in bringing peripheral countries’ yield spreads under control all seem to have come from the ECB and its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, or PEPP: