In a single day in early August, yields on $700 billion of global debt went into negative territory, raising the specter of negative interest rates in the U.S. Until this summer, most experts viewed negative rates as a problem confined to parts of the developed world challenged by slow growth and aging demographics.

By August 14, 10-year U.S. Treasurys were yielding 1.7%—a lower rate than 2-year Treasurys for the first time since 2007—and the 30-year long bond at 2.07% hit its all-time low. Incongruous as it might appears, there are real fears that an economy with a 3.7% unemployment rate and 7 million job openings was stalling out.

Even if America is one of the bright spots in the global economy, that’s little cause for celebration. Tens of millions of working-age Americans aren’t even looking for work. Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell’s misreading of the U.S. economy’s strength in 2018 was a major blunder, according to David Rosenberg, chief market strategist of Gluskin Sheff.

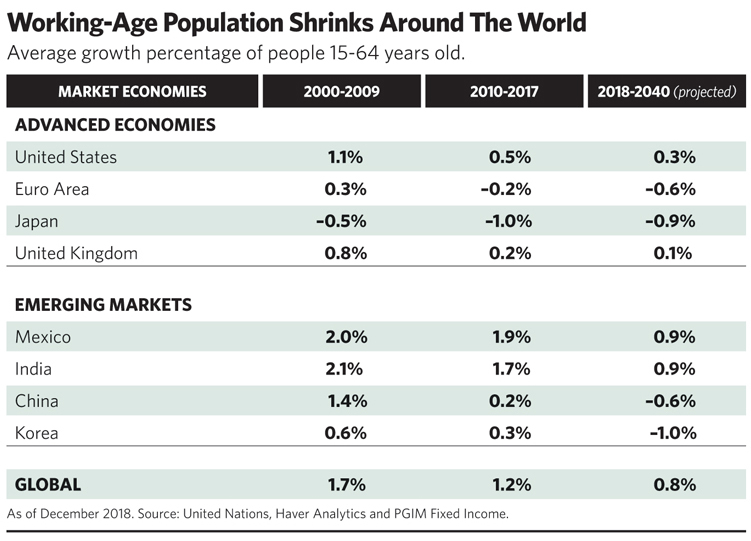

Many interpret the persistent low interest rates as the result of distorted monetary policy arising from the Great Recession, a failure that turned out to be punishing for savers and retirees. Other believe there are larger forces at work, especially declining population growth leading to economic stagnation on a global level.

Arguing that the prospect of negative rates in America was “no longer absurd,” Joachim Fels, global economic advisor at Pimco, cites other factors fueling the phenomenon—longevity and technology. “Rising life expectancy increases desired saving while new technologies are capital-saving and are becoming cheaper—thus reducing ex ante demand for investment. The resulting savings glut tends to push the ‘natural’ rate of interest lower and lower.”

Since the financial crisis, the U.S. savings rate has doubled to 8%. That means American consumers should be in a stronger position to deal with the next slowdown.

Changing Consumption Time Preferences

In recent years, financial advisors have witnessed many of their more affluent clients stand classical economic theory on its head. Traditionally, the time preference consumption theory held that people preferred today’s consumption over next year’s and thus had to be paid a higher interest rate if they were to be enticed to save. “It can be argued,” Fels writes, “that in affluent societies where people can expect to live ever longer and thus spend a significant amount of time in retirement, more and more people demonstrate negative time preference, meaning they value future consumption during their retirement more than today’s consumption.”

Longevity Spawns Specter Of Negative Rates

September 1, 2019

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment