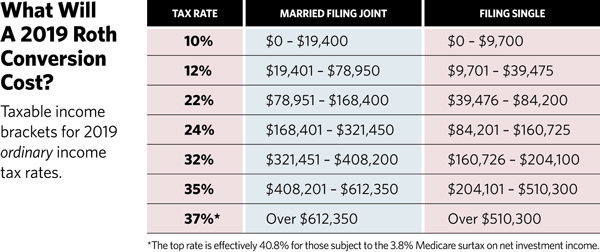

Clients will be asking you about 2019 Roth conversions as the year winds down. They’ll want to know whether they should convert their IRAs to Roths, how much should they convert and most important—how much will it cost?

What will you tell them?

For 2019, you’ll need to know how to more accurately project the tax cost of a conversion because once it’s done, it cannot be undone. Conversions can no longer be recharacterized, so once the funds are converted, the tax bill is set in stone. You have one chance to get this right.

This should be well known by now to financial advisors, but a good chunk of taxpayers did not get that memo. The tax returns for 2018 were the first ones filed under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which, among other things, eliminated the ability to reverse Roth conversions. Poor projecting meant many people got stuck with much different tax bills than they expected for 2018 conversions. That was understandable because it was tough to compare the rates under two different tax regimes (one for 2017, and then one for 2018, when many parts of the previous law had changed or been eliminated). Even CPAs got caught flat-footed on this and really did not see the true tax effect until the returns were prepared the following year, when of course it was too late.

This year, it will be a bit easier to see Roth conversion effects since we can at least compare them with 2018’s returns—as long as most other income and deduction items are relatively similar. Yet there are still items that confound the best 2019 projections.

Some changes unexpectedly increased the tax cost of the Roth conversion. Others reduce the tax bill. That has created an opportunity for filers to capitalize by converting more funds than they might have planned to.

Here are the five most misunderstood tax effects of Roth conversions.

1. Capital Gains

This one is not new, but the larger, more favorable capital gains tax brackets left some thinking that a good portion of their long-term capital gains would fall under the 0% bracket and escape taxation. Not so! For most Roth converters, each dollar of ordinary income (including Roth conversion income, wages, interest, etc.) reduces the benefit of the 0% capital gains rate. Under the tax law, ordinary income is taxed first, which uses up the lower long-term capital gains brackets. Anyone with other income besides long-term capital gains receives little or no part of the 0% long-term capital gains rate, so don’t count on that for your tax projections. Of course, you can always offset these stock gains by harvesting losses. It can also pay to put off taking large capital gains in the same year you’re doing a Roth IRA conversion; instead, take those gains in a future year when ordinary income might be lower. For example, if most IRA funds are converted into a Roth IRA, when the taxpayer is age 70½ his or her required minimum distributions will be substantially reduced, lowering taxable ordinary income and allowing more long-term capital gains income to fall into the lower long-term capital gains brackets.