It’s been almost two years of sluggish markets and a rising regulatory menace, and it’s likely investment advisors would find themselves squeezed. The threat of new U.S. Department of Labor rules determining how advisors can handle retirement assets sent a chill through the profession, even though the rules impact advisors with brokerage licenses more severely than RIAs (brokerage firms have already answered the final rules that arrived in April with lawsuits).

Nor were the stock markets friendly to advisors. After several years of double-digit returns, the S&P 500 was up 1.4% in 2015, including dividends. Since mid-2014, domestic equities have essentially gone nowhere.

To view FA's 2016 RIA Ranking and the 50 Fastest Growing RIAs, click here.

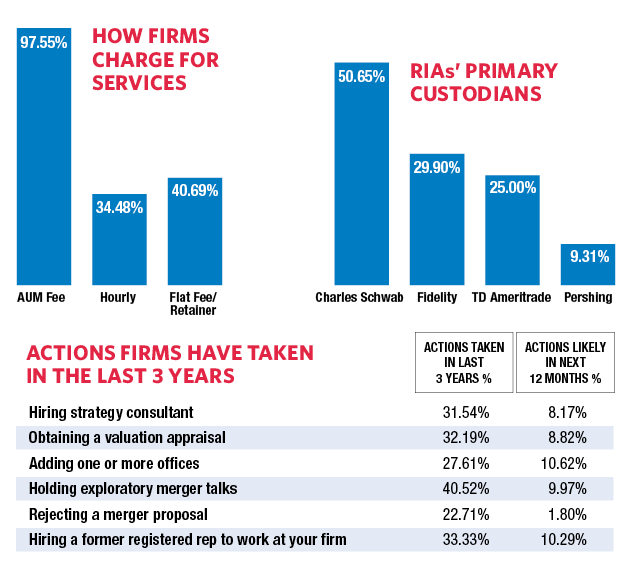

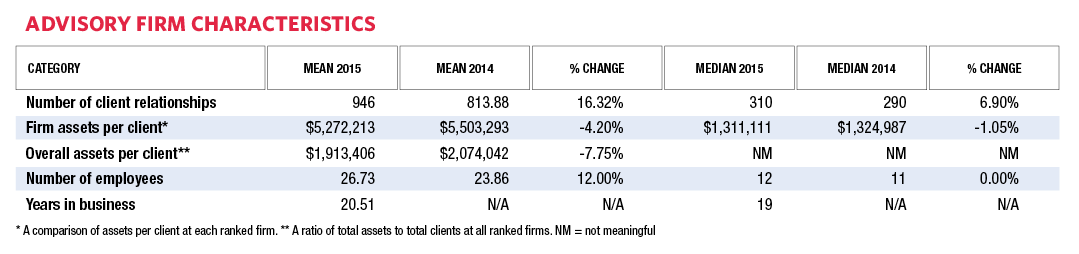

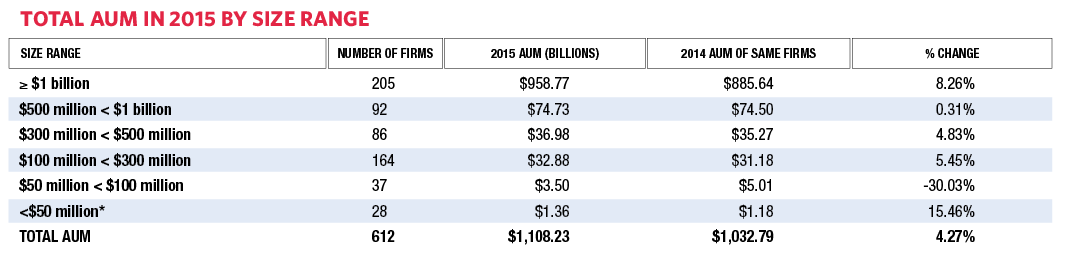

Among the 612 RIA firms surveyed by Financial Advisor magazine, more than one-third, 219, said they saw assets under management shrink last year. The average amount of firm assets per client fell 4.2% from $5.5 million to $5.27 million.

“Poor market conditions for the past two years [hurt],” says a principal at one firm in the survey. Other responses should remind advisors that their firms are always vulnerable to staffing and succession issues. One advisory with more than $2 billion in year-end total assets noted, that the “loss of a single senior advisor in 2015 negatively impacted [the firm’s] AUM by over $400 million.”

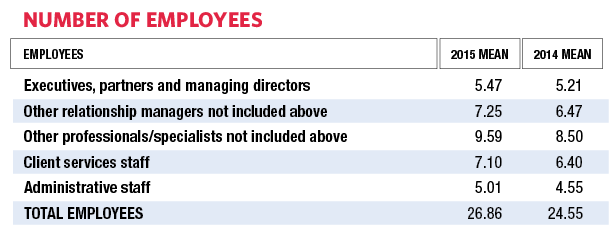

There are other suggestions, however, that the volatility and regulatory burdens borne by other channels are the registered investment advisor’s gain. The average number of client relationships rose more than 16%, to 946.67 in 2015 from 813.88 in 2014, as the very big firms continued to get bigger. The average number of employees at the firms, according to the survey, rose to 26.73 from 23.86.

“The local and national economy have played a large role in the growth of our business,” says a principal at one firm, “mostly because of the recent market volatility and the effect that has had on client emotions and willingness to move assets.”

Technology plays a role in hindering growth as well. Says the principal at one firm with a little more than $200 million in assets: “The thing that has most hurt our firm in our aim to grow our asset base has been the building out of the infrastructure from scratch since we [are] such a young firm.”

But chaos, as the roguish character Littlefinger from Game of Thrones once noted, also creates a ladder and opportunity. One owner of a business with $25 million in assets in 2016 noted flatly: “Market volatility has helped.”

And the new DOL regs were seen by many not as hindrance but as validation—the stamp of approval for a fiduciary approach they were already taking. Says one advisor: “I believe we will benefit from the DOL policy because more clients will come to realize that their broker did not treat them as well as they thought.”

Some firms viewed the stagnant business environment as an opportunity to re-examine their business strategy and make some tactical shifts to invest in the future. Massey, Quick & Co. of Morristown, N.J., was established a decade ago as a high-end firm and grew quickly to $2 billion in assets under management, attracting clients with an average of $11 million at the firm, according to managing partner Joseph Belfatto.

But those types of clients typically gain their wealth via some sort of liquidity event, and since the Great Recession, there haven’t been as many initial public offerings or mergers and acquisitions. So Massey Quick dropped its $5 million minimum and decided to target the emerging affluent, reaching out to business owners, successful women and younger executives.

Belfatto says his firm is gaining clients from banks and brokerages, but some younger clients are looking to diversify among advisors and not keep all their assets with any single institution, another reason the firm decided it could do better without a high minimum. While adding clients, Massey Quick saw its AUM decline last year, primarily because it restructured a third-party relationship.

Many clients are wrestling with conflicting goals. In a flat market, they want higher returns and capital preservation. That’s one reason many more affluent clients are comfortable with the firm allocating about 10% of their clients’ wealth to private equity. “In private equity, you get paid for illiquidity, but they have to be comfortable locking up their money for eight to 10 years,” Belfatto says.

With RIA firms finding organic growth to be a major challenge, mergers and acquisitions are emerging as an alternative path to expansion. “There are tons of conversations happening,” notes Steve Levitt, a managing director at Park Sutton Advisors, which focuses on M&A advice for RIAs with between $300 million and $5 billion in assets.

If a firm decides to sell itself, it can find many interested buyers. But Levitt adds that doesn’t mean the firm will always meet an ideal cultural fit or consummate a deal.

One sign of the times is the re-emergence of banks as potential buyers of RIAs. “Everyone from banks to RIAs is finding growth challenging, and RIAs have stable cash flows,” Levitt says.

Still, the big trend in the RIA world has been mergers among equals and tuck-in acquisitions where a big firm finds another with at least one senior partner looking to retire. Take Jeffrey Powell, a managing partner at Polaris Greystone Financial Group. He started his firm Polaris Wealth Advisers in 1998, and through a merger last October with Greystone Financial Group in Troy, Mich., went on to create a $995 million AUM national firm with offices in Troy; Houston; San Rafael, Calif.; and Irvine, Calif. (Polaris had about $650 million on the eve of the merger and was also sub-advising more in assets.) Powell says he had a long-standing relationship with Todd Moss, his new business partner at Greystone and had been sub-advising some of his clients.

The average net worth of the firm’s clients is just under a million, he says. One of Greystone’s partners was retiring, so the timing of the merger made sense for that reason. “It was not a grow-or-die type of thing in that regard,” he says.

When asked whether their firm had been part of a merger or acquisition in the past three years, 103 of the 612 firms in the survey said yes. “There will be a consolidation as you continue to see the average owner of an RIA continue to grow a year older each year,” Powell says. “Which means you really aren’t having much of a backfill of new advisors that are entrepreneurial and starting their own firms to either be there as a succession plan or as a mergers and acquisition partner. We structured ourselves purposefully to be able to take on other firms under our wing … [and] create economies of scale. There are huge benefits from having one compliance officer, one HR officer, having the investment management all under one roof.”

Even in challenging times, organic growth is possible. Seattle-based Brighton Jones managed to grow its asset base 13.8% last year to $3.3 billion and its CEO, Jon Jones, says the firm’s biggest challenge is finding and hiring “really good CFPs.” The firm has a staff of 100 people and is looking to hire another 20 this year while realistically expecting about five to leave.

Like other firms its size, Brighton Jones recognizes that the law of large numbers means the firm is going to have to get better at sales and marketing. However, it is big enough to invest in that area, though Jones acknowledges the firm “is in Inning One” when it comes to sales.

The thriving Seattle economy works to Brighton Jones’ advantage, since there is no shortage of successful young people in their 30s and 40s. While many RIAs have focused on NextGen clients, Jones reports his firm has added lots of clients’ parents who are still with brokers trading stocks and not adding much value.

But the biggest initiative at Brighton Jones is fleshing out what it calls “vocational freedom” planning, or having the assets to work at “what you want to do and care about,” Jones says. A number of other firms, like Edelman Financial and Halbert Hargrove, are doing the same thing and some believe that what can be termed late-stage career planning will become a major determinant of which firms thrive over the next two decades.

Camden Capital, a Los Angeles firm, had already set itself up for growth in 2015 with its previous hires of teams, including four new professionals in Florida in 2013, as well as local professionals. Camden launched more than 12 years ago with only $25 million in assets. It now has about $1.7 billion. “We got to the billion dollar level and we felt it was time to start to expand the practice a little bit,” says founder and CEO John Krambeer.

The firm started “with me as the only rainmaker,” says Krambeer, a veteran of Merrill Lynch, where he’d started his career at the switchboard and worked his way up on the brokerage side of the business for 16 years, eventually going on to help build the high-net-worth business. “I was the first inside-Merrill person to cross over from the retail version of Merrill’s business into the high-net-worth space, which it created in the late 1990s by acquiring a lot of those very strong teams that came from Goldman and JP Morgan.”

But he couldn’t always find the right solution in Merrill’s product delivery system. There was at the time no comprehensive reporting system for all of a clients’ assets at other firms, he says, nor for other types of products such as annuities. And the transition to higher-net-worth clients meant it was hard to service somebody with a $100,000 and $100 million the same way. Tailoring service to a certain client’s needs was hard.

“The system has opened up,” he says of the reporting abilities at the independent firms. He says the firm has no minimum accounts. The referral relationships mean a client with $100 million might want to refer a good friend with only a million, and Krambeer says he’s brought in team members that can service both. “We’ve stayed true to that and I think it’s served Camden well.” The firm’s average size client has $15 million to $20 million, and he’s developed a niche with attorneys and people in real estate, as well as entrepreneurs who have cashed out.

The equity market has been tough on RIAs, he says, “when you’re managing for defense and managing for preservation of capital to have significant returns these last two years. It’s been very, very tough,” Krambeer says. “That’s not making it easy on us either. It’s not like we have a magic allocation that nobody else knows. The only way to make a lot of money in the last two years would be to basically have a concentration of U.S.-only stocks. And if you’re in the business of managing risk it’s hard to do that.” To that end, the firm has tried to separate itself by turning to more private fund firms—real estate, distressed municipal bonds or private equity.

Managing expectations means that advisors need to be realistic about clients’ mind set. James Rudd, principal and CEO of Ferguson Wellman, a $4.3 billion RIA in Portland, Ore., tries to get clients to focus on the medium-term, five to seven years, reasoning that if one talks about a 10-year time, “my experience has been that we [can] lose them.”

A former president of the San Francisco Fed’s Portland branch, Rudd argues that winning the investment game is about “practicing patience and sticking to quality,” while being willing to tolerate no gains or some losses “in order to be there when the environment improves.” At present, Ferguson Wellman is stressing a dividend value portfolio, while increasing its allocation to corporate bonds and cutting back on low-yielding Treasurys.

It’s hardly too late to start an RIA; in fact some former executives from the institutional money management world are doing exactly that. Auour Investments, a Wenham, Mass., firm, was one of the fastest growers in the survey, seeing almost 90% asset growth in 2015 and almost doubling its reported client relationships from 50 to 100. The firm uses ETF strategies and a dynamic investment model that it offers directly and through non-affiliated advisors.

Joseph Hosler, the firm’s managing principal, says that wiggle room allowed the firm to go to 60% cash positions in one strategy last year (on average it goes to 50% in all strategies) and be in a good position when the market went down a few months ago. The young firm, founded in 2013 by Hosler, Kenneth Doerr and Robert Kuftinec, veterans of firms including Putnam Investments, Evergreen Investments and Babson Capital, started with money from friends and family, but later built on word of mouth. Though the firm is a money manager, it can also take on CFO capabilities for high-net-worth clients.

“Last year, one or two [non-affiliated] advisors moved a lot of their book to us, but on the direct [wealth management] side we had a lot of families starting to monetize other assets and move it into our firm,” he says. “We took on a lot more of [a] CFO role for clients moving out of hedge funds and real estate.”

Alan Goldfarb, a former CFP Board Chair, and Diana Bacon merged their Dallas firms last year, Beacon Financial and Financial Strategies Group LLC, to forge a firm with more than $27 million in assts.

Goldfarb had been running a wealth management group inside a large Texas accounting firm, and fled the culture clash. “Their objective was just to raise money and mine was to do comprehensive planning.” His unit at the accounting firm had over $350 million, most of which had come from outside the accounting firm, he says.

He said the 2015 RIA environment made having a backup partner seem like a good idea. There’s an almost three-decade age gap between Goldfarb and Bacon: More clients were in the accumulation phase at her firm, more in the distribution phase at his. Clients of Goldfarb were asking questions like “What if you get hit by a truck?”

“I’ve been on my own since 2006,” says Bacon, who has been practicing 18 years. Her client base tends toward single women, divorced women and same-sex couples, and she and Goldfarb are currently looking at junior planners with similar backgrounds. “We want diversity in our planners because it’s organically going to get us a diverse client base,” says Bacon.

Derek Williams is among those who says fiduciary issues have presented opportunity for his firm, the Williams Wealth Management Group in Bradenton, Fla., which saw assets grow by about 15% in 2015 to $33.5 million by year’s end. The fiduciary rules “opened up some additional talking points” with clients, he said in an interview with Financial Advisor.

“My story and our firm story is that we’ve been independent from Day 1,” he says. “So it’s not like the legislation changed our business. It’s more like the industry came to us. … [It’s] validating that we’re doing things the right way while other firms are having to change their business model to adjust to the environment.”

The biggest influx of business right now, he says, which he says could double his business, is a new separate entity he’s created called Fiduciary Shield for 401(k) plans. “We hired one of the top ERISA attorneys in the country to help us draft a contract and we are able to go out now and help [retirement plans] get in compliance, which can lead to asset management business. Everything is fully disclosed, but it’s a way for us to help essentially 401(k) plans comply with the new rules because so many of them are out of compliance. That is a segment of our core business, which was business retirement plans. That’s just kind of gone viral for us because there are very few true independent solutions out there. There’s a lot of canned products out there and there are a lot of people who are offering services—3(16), 3(21), 3(38) services—that are frankly not compliant themselves. They were getting away with it and now they can’t. There’s a microscope on that business.”