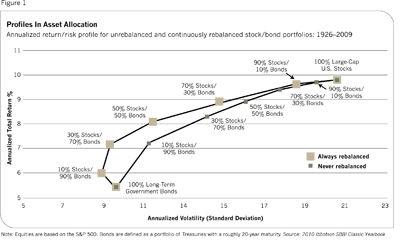

A simple example is the long-term history of various blends of domestic stocks and Treasury bonds. Unsurprisingly, higher allocations to equities are linked with higher return, according to Ibbotson Associates. But they are also linked to higher risk (the annualized standard deviation of return). History suggests, too, that mechanical rebalancing juices the results a bit (see Figure 1).

Holding a basic portfolio of U.S. stocks and bonds over the long haul generated an annualized return of roughly 6% to 9.5%, depending on the exposure to stocks and the rebalancing rule. Over shorter periods, the results can and do vary quite a bit more. In the decade through 2009, says Ibbotson, a 50/50 unrebalanced mix of stocks and bonds delivered less than 4% a year-a sharp drop from the nearly 14% return for the previous decade. Adding a bit of cash (Treasury bills or the equivalent) lessens the volatility, though it also slightly hampers return.

Looking at portfolios in this way suggests that there are several basic strategies for enhancing return. One is buying and holding a different asset allocation, or managing asset allocation dynamically. Another possibility is picking individual securities within the asset classes. But the task is tougher than a simple analysis would suggest.

Defining "The Market"

A proper reading of modern portfolio theory requires looking beyond a portfolio of U.S. stocks and Treasury bonds. In theory, the market portfolio holds all assets, weighted by market value. The true market portfolio isn't practical, of course, but we can build a reasonable if less-than-ideal proxy.

For example, imagine it's May 2000. The stock market has wobbled a bit, but it's generally been on a tear for several years and recently hit an all-time high. In fact, it was the beginning of a deep, multiyear bear market for equities. But let's say you invested in a broadly diversified portfolio at the time-at roughly the stock market's peak-with this allocation:

20% U.S. stocks (Russell 3000)

20% Foreign developed-market stocks (MSCI EAFE)

20% U.S. bonds (Barclays Aggregate)

20% Foreign developed-market government bonds (Citigroup WGBI ex-U.S.)

5% Emerging market stocks (MSCI EM)

5% REITs (MSCI REIT)

5% Commodities (DJ-UBS)

5% Cash (Citi 3-month T-bill)

Most of the allocation (80%) is evenly split between stocks and investment-grade bonds in the U.S. and foreign-developed markets, which roughly equates with a passive weighting based on market values. The remaining 20% is divided evenly across emerging market stocks, REITs, commodities and cash. For the decade through May 2010, this unmanaged strategy earned an annualized total return of 4.7% with an annualized volatility (standard deviation) of 9.2. By comparison, U.S. stocks (Russell 3000) were basically flat over the same decade with about twice the volatility. Meanwhile, U.S. bonds (in the Barclays Aggregate) rose by 6.5% over the same stretch with annual volatility of about 4.0.

Could you have done better? Maybe. For instance, rebalancing the portfolio would have boosted return modestly, depending on when and how you rebalanced. Some studies show that rebalancing over time can add 50 to 100 basis points in the long run. That implies you could have earned 5% or more a year over the past ten years with our hypothetical portfolio if you used some simple rebalancing rules.

Let's stop and consider a 5% return over the last decade as compensation for a) diversifying broadly, and b) rebalancing the mix every year or so. Not bad for a strategy that requires no skill per se.