The “Sell in May and Go Away” maxim originated in London under a slightly modified phrase: “Sell in May and go away, come back on St. Leger’s Day.” The St. Leger is a famous fall horse race in the U.K. that dates back to 1776. The premise behind the saying is that investors should sell their equity positions in May, enjoy the summer months and avoid seasonal market weakness, and then come back to the market when seasonality trends become more constructive in November.

Why is the phrase so popular? Math and marketing may have something to do with it—areas Wall Street is pretty good at. Other than an easy adage to remember, the May through October time frame has been the worst six-month return window for the S&P 500 since 1950, as opposed to the best-performing six-month return window from November through April. This historical seasonal pattern has been consistent enough—and the phrase popular enough—that it may have become a self-fulfilling prophecy over many years.

While the U.S. might not have the St. Leger race, we did celebrate the Kentucky Derby over the weekend, and the thought of “enjoying” some golf and beach time this summer sounds appealing, but we don’t wholly subscribe to going away from the market over the next six months.

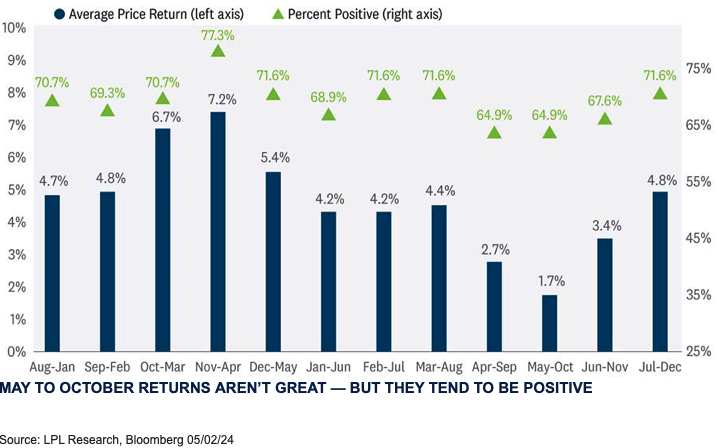

The table below highlights rolling six-month price returns for the S&P 500 across all 12-month periods since 1950. And while the May through October time frame has historically underwhelmed with an average gain of only 1.7%, returns importantly have been positive 65% of the time. Of course, that doesn’t stack up very well compared to the 7.2% average gain between November and April, but other technical and fundamental factors point to upside potential beyond the average 1.7% gain during this year’s “Sell in May” period. Longer-term momentum indicators point to more potential upside for stocks before year-end, earnings continue to surprise to the upside with estimates holding steady (estimates typically fall 2–3%), while economic activity is humming along at a solid pace. Furthermore, Friday’s goldilocks jobs report showed labor demand slowing but still growing and cooling wage growth, helping raise the probabilities for two rate cuts by year-end.

Recent Years Have Yielded Better Returns

More recently, the month of May and the “Sell in May” time frame have yielded better results. Over the last 10 years, monthly returns in May have averaged 0.7%, with nine of the last 10 years producing positive monthly returns. This compares to the longer-term average May return of only 0.2%.

As highlighted below, May through November average returns have also been more constructive at 4.0%, with 80% of periods generating positive results.

Finally, with the election now only six months away, we analyzed “Sell in May” returns during election years since 1952. The S&P 500 generated an average gain of 2.3% during these periods and finished higher 78% of the time.

What About Volatility?

If you plan to stay invested through the “Sell in May” period—LPL Research recommends holding a neutral equity market position—volatility could be the price of admission. The CBOE Volatility Index, more commonly referred to as the VIX or “fear gauge,” historically advances from July through October, often peaking in late September or early October.

For reference, the VIX represents implied 30-day volatility derived from the aggregate values of a weighted basket of S&P 500 puts and calls over a range of strike prices. In general, the higher the VIX, the more fear and uncertainty there is in the market, and vice versa.

The monthly seasonality of the VIX is highlighted below.

Monetary Policy Remains In The Driver’s Seat

Seasonality data can provide important insights into the potential market climate, but it doesn’t represent the current weather. And when it comes to markets, monetary policy has the power to make it rain or part clouds into sunshine. However, as we witnessed at last week’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, policymakers appeared to be in no rush to cut rates, citing inflation’s lack of progress toward their 2% objective. Perhaps more importantly, Fed Chair Jerome Powell helped remove the dark clouds of a potential rate hike and stagflation fears hanging over the market, stating he doesn’t see the “stag” or the “flation” risks that have recently made headlines. While the meeting was less hawkish than feared, the Fed’s message did strengthen the higher-for-longer narrative, meaning we may not get a rate cut until September.

The current pause has now reached 280 days—the second-longest in modern market history, trailing only the 2006–07 pause that reached 446 days. The average Fed pause has lasted 146 days. The bearish angle on this statistic is that over the past 50 years, the S&P 500 has only gained 6% on average during pauses, and the gain during the current pause has reached 12.4%.

However, on a more positive note, over the last six pauses going back to 1989, the average gain has been 13.1%. This isn’t just cherry-picking—the last six pauses are the longest, which more closely mirror the ongoing pause. The 2000–01 pause was the one long pause when stocks fell. The S&P 500 lost 7% during that pause that was marred by recession and devastating accounting scandals.

Bottom line, long pauses aren’t typically bad for stocks. It’s when the Fed is forced to cut because of economic weakness that stocks tend to sell off—not the environment we’re in today.

Summary

Seasonality trends point to a potentially softer period of market performance over the next six months. However, the “Sell in May and Go Away” maxim has been more rhyme than reason as the market historically trades higher from May through October, especially over the last 10 years when returns averaged 4.0%. The price for holding stocks during this period is historically high volatility (September and October are the most volatile months, as measured by the VIX). Finally, seasonality data is only one potential factor influencing markets and is far second to other key fundamental drivers such as the economy, earnings and monetary policy.

Adam Turnquist is chief technical strategist at LPL Financial. Jeffrey Buchbinder is chief equity strategist at LPL Financial.