Raghuram Rajan has decided not to seek a second term as the governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and instead will return to the University of Chicago (U of C) after September 2016. The departure of any official is never a question of “if” but one of when and how. Recent events suggest that the Indian government pushed him out.

Although the RBI has had many distinguished governors in its 81-year history, Rajan is certainly the most globally well-known and conspicuously independent of the lot. He had a long academic career at U of C’s Booth business school, spent three years as chief economist of the International Monetary Fund and was one of the first voices to warn in 2005 of the impending global financial crises. He also spent a year as the chief economic advisor to the Indian government, rounding out a stellar background that he brought to the RBI’s helm.

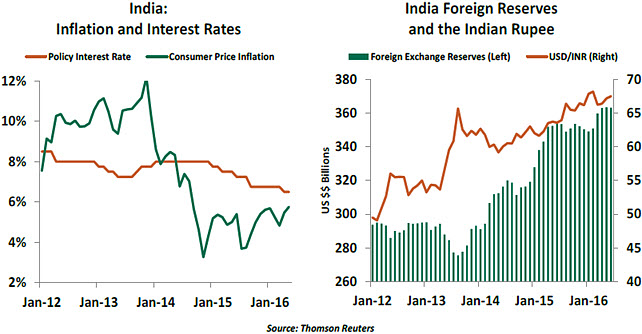

Joining the bank during the so-called “taper tantrum” in September 2013, Rajan had a crucial role in stemming a currency crisis in India. Since then, he has focused on taming inflation, stabilizing the rupee, building foreign exchange reserves, introducing inflation targeting, and cleaning up non-performing loans in the public sector banking system.

At most times, monetary policy is not rocket science. There is a standard policy reaction for taming inflationary expectations, or to stop a run on the currency. However, personality matters when tough choices are at hand. Rajan was able to leverage his credibility with the international financial community to push ahead with decisions that would otherwise earn the wrath of the government or vested interests.

By objective standards, his tenure was a great success. Therefore, it came as a shock when, after consulting the government, he decided to not seek a second term.

Since the economic liberalization of 1991, the RBI has earned a reputation for independence. Its standing may not be at the level of central banks in developed markets, but the RBI certainly stands head and shoulders above most of its peers in the developing world. The RBI’s leaders and Indian finance ministers have publicly disagreed in the past, but every RBI governor in the last 25 years was granted a second term, despite regular changes in government.

The decision to elbow out Rajan suggests a new regime is in place. His opponents are not fans of monetary restraint, and speculation swirls that “big business” — hurt by the cleanup of the banking sector — forced the government’s hand. Rajan may not have helped himself by commenting on social issues or by being too frank about India’s economic situation.

But his departure shows the government in a poor light, suggesting a lack of understanding about the importance of a credible and independent central bank governor.

The incoming governor not only must live under Rajan’s shadow but will have to fight the perception of being a rubber stamp. A quick announcement of a credible, independent and articulate RBI governor will be essential to India’s continued economic success.

The Power of Crowdsourcing