People in ancient times sought answers about the future from Pythia, the Oracle of Delphi. Today, polls, statistical models and prediction markets are the means used to foretell the future. The latter method played a central role in the run-up to the Brexit vote – and failed miserably.

In prediction markets, participants trade in contracts whose payoff depends on the outcome of future events. A prediction market asks a yes/no question. “Do you think Trump will be elected president?” “Do you think ‘Star Trek Beyond’ will be a success?” The answers are then turned to a probability. If 65% answer “yes,” that becomes a contract you can buy or sell. If the ultimate payout is set at $10, you buy the contract at $6.50. If it turns out right, you make $3.50; if you are wrong, you get nothing.

Prediction markets work with real money, funny money, small prizes and vouchers. The “odds” they produce are not just a product of how many people are on one side or the other but also how much they are willing to wager on the outcome.

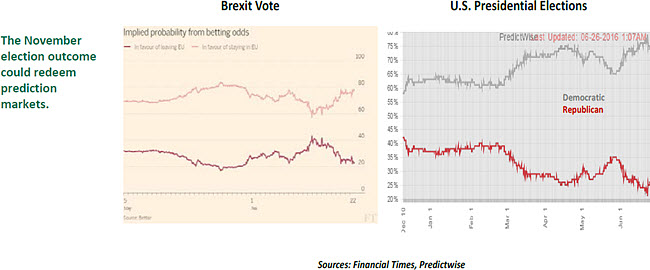

Research indicates that prediction markets have produced better forecasts than other methods in a range of domains, including elections, sports, business propositions and entertainment. But they failed with the Brexit vote. Speculation around the cause of the failure centers on large bets placed by a small community on “Remain” that was very slow to adjust its initial beliefs, even as the “Leave” movement gained momentum.

At the moment, betting markets suggest that Donald Trump has just a one-in-four chance of becoming the next U.S. president. We’ll see if those odds prove correct next November.

Carl Tannenbaum is the chief economist for Northern Trust.

Asha Bangalore is senior vice president and economist at Northern Trust.

Ben Trinder is a London-based analyst with the country risk unit at Northern Trust.