With the market capitalization of the Shanghai, Shenzhen and Hong Kong exchanges totaling roughly $13 trillion,1 the size of the opportunity in China’s equity markets has attracted attention from investors worldwide. With the growing inclusion of China’s domestic A-share market into major global indexes, portfolio allocation strategies are set to change. As news headlines increasingly move the market in China over the short term, however, investors often need to look beyond both the headlines and standard screens to contextualize the relevant corporate governance and environmental, social and governance (ESG) information when investing in this market over the long term.

During conversations with investors, we often have found that hesitation to invest in Chinese companies can stem, in part, from a perception of poor corporate governance. We would argue that this perception is outdated, as we believe corporate governance has improved substantially. At the same time, active security selection is required to avoid pitfalls and investors must keep a number of nuances in mind. While corporate governance in China differs from the rest of Asia, our experience tells us that one cannot apply a blanket approach to corporate governance even within a single country or region. Each market has its own approach to corporate law, shareholder rights and regulation, which makes measuring broad portfolios on corporate governance both challenging and of limited value. Understanding certain corporate governance intricacies, progress on reforms and picking the right companies is critical.

Strong corporate governance and good ESG practices may show little direct link with short-term stock performance, but we believe they are critical to delivering long-term, risk-adjusted shareholder value. In China, we are seeing positive change on a variety of ESG factors, especially around state ownership, shareholder friendliness, ownership and control structures, disclosure, board composition, environmental stewardship and corporate conduct.

REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT HAS MADE SIGNIFICANT IMPROVEMENTS

Government-Led Reforms Promote Better Governance

The evolution of corporate governance in China has gone through several stages, with fundamental reforms over state ownership and company law mainly developing in the 2000s with the adoption of various developed market regulations, such as supervisory boards and shareholder protection. China is in the process of establishing its own model of governance, with the 2018 China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) revised Corporate Governance Code the first major indication of how this will develop. The new code promotes diversity, underscores the role of minority shareholders, promotes cash dividend distribution and generally strengthens ESG principles.

Policymakers have introduced laws and policies in recent years to promote better ESG practices and disclosure among corporations. Given that top-down planning features prominently in China, these regulatory initiatives are likely to further drive rapid ESG uptake by both investors and issuers. China’s regulatory fund body, the Asset Management Association of China, has announced new measures to advance the inclusion of ESG factors within the country’s public fund houses.

Corporate Governance and the Security Markets of China

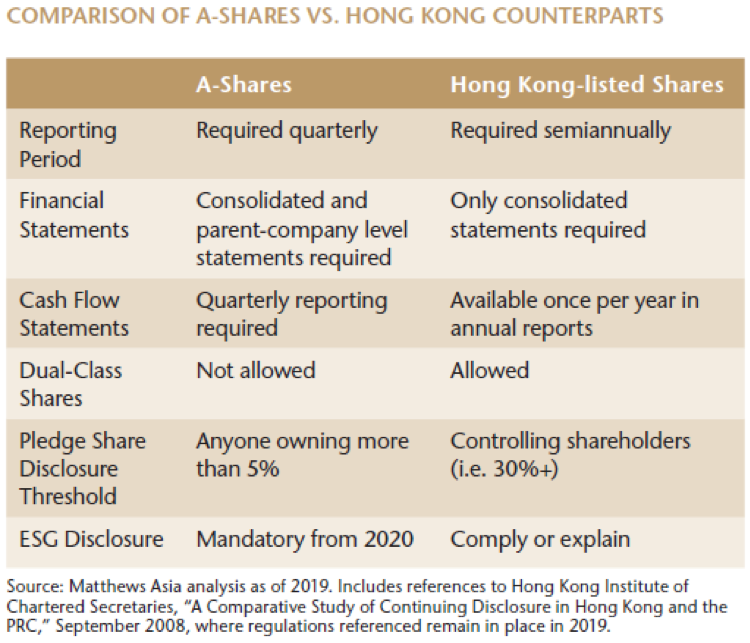

China has taken many steps to give investors more confidence to invest in the country’s capital markets by focusing policy on corporate governance reforms. Policymakers have amended or issued key rules and guidelines over the past years related to financial reporting, disclosure of substantial ownership stakes and director trading. Fair and relevant disclosure of financial and operational information is an important component of good corporate governance. In some respects, A-share listed companies (those that trade in China’s domestic stock markets) are outdoing Chinese companies listed in offshore markets in areas such as comprehensive disclosure requirements. A-share companies also are subject to stricter regulation on potential conflicts of interest (see table below).

For example, companies listed in the mainland Chinese stock market are not legally permitted to issue multiple share classes with unequal voting rights, yet the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in April 2018 opened the door for dual-class shares, which often are used as a way for founders to enhance control.2 Another topic surrounds the disclosure of pledged shares, where the rules in China are more onerous than regional standards.3

Enforcement and engagement also are on the rise. Bloomberg reported that in the first months of 2019, China’s stock exchanges stepped up scrutiny of listed companies to address corporate governance concerns, sending 23% more queries to local firms, which was 62% more than in the same period in 2017. The queries focused on irregularities in the firms’ financial results, inadequate information disclosure and relations with controlling shareholders with the goal of improving the credibility of China’s capital markets for international investors.4

DIVIDEND PAYOUTS RISING ACROSS MANY SERVICES RELATED SECTORS

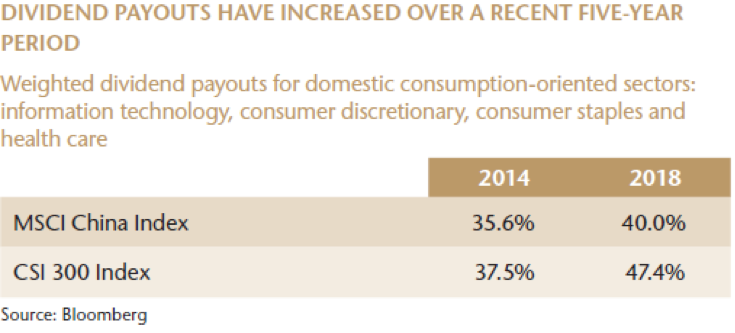

Although there is no shortcut to a holistic review of corporate governance quality, we find a company’s willingness and ability to pay dividends consistent with one’s growth stage and cash flow profile an effective indicator of good corporate governance. Thanks to the deeply rooted culture of income distribution, 87% of Chinese companies in the MSCI China Index paid dividends in 2018, which provides tangible and verifiable data points about how companies treat minority shareholders. Furthermore, investors who are skeptical about accounting quality in China can get some reassurance from a company’s dividend record, as dividends have to be backed up by real cash flow. Many controlling shareholders of Chinese companies like the dividend structure as it creates an ongoing stream of income for the owners to support their financial needs outside of the listed company. Through this structure, we find that minority shareholders often enjoy fair participation in profits and transparency in capital allocation decisions.

China’s State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) Proactive Governance Reforms

The unique nature of the state and government is often discussed when it comes to corporate governance in China. While concentrated ownership dominates this market, this phenomenon is hardly unique to China. In fact, as of 2018, the broad MSCI Emerging Markets Index included 71% of constituents with concentrated ownership. State-owned enterprises (SOEs), due to their large size, still have a high representation in major mainland China indices even as their revenue share has declined in many sectors. As a result, a passive approach to investing in China could lead to indiscriminate exposure to SOEs in investor portfolios. Meanwhile, active investment strategies have the advantage of investing more in dynamic companies that are not owned by the government. As active managers, we are not categorically opposed to investing in SOEs but we believe they need to be approached very selectively. We invest in SOEs with attractive assets, quality management and positive progress on governance reform.

Over the past six years, policymakers have promoted efficiency and capacity reduction in the historically state-concentrated steel and coal industries, leading to a reduced headcount in both. The State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC) has said that local governments should get out of competitive sectors where there is little strategic need for state ownership, and encourage local governments to sell down controlling stakes and undertake more M&A and restructuring. Similar trends in a number of sectors reflect the market-share gains of companies without state ownership as China shifts to its consumption- and service-oriented economy. Many of these companies, especially within the services and consumer sector, have been heeding the guidelines of the revised Corporate Governance Code and increasing their cash dividend distributions to shareholders.

POLICY FRAMEWORK SUPPORTS ENVIRONMENTAL PROGRESS

Much improvement can be seen in China’s policy framework on environmental areas as well. China’s leaders have understood that transforming the world’s second-largest economy from one dependent on highly polluting heavy industry to one focused on clean energy, services and innovation is essential, not only to the future of the planet, but to China’s own prosperity. Policymakers’ focus on green policies has led to China’s pivotal role in environmental protection, which can been seen through a slew of new regulation, commitments and investments in innovation. Often, the government plays the role of a “gatekeeper” in corporate governance and push toward ecological civilization. The central government’s environmental-inspection program launched in late 2015 with the full authority of the government’s top leadership. Regulators have been serious about closing down players who are not compliant with environmental norms. Thousands of government and state-enterprise officials as well as companies have been held to account in these inspections with more public naming and shaming of environmental violations.5

Availability of ESG data is improving

Many of the improvements have been around data transparency and the disclosure of ESG-related information from both companies and third-party monitoring. One example can be seen in the number of companies issuing independent social responsibility or ESG reports. While low on a global basis, the number has risen from 200 in 2008 to more than 3,000 today.6 ESG reporting is expected to be a mandatory disclosure requirement in 2020 by the CSRC.7 In addition, China’s Emission Trading Scheme announced in 2017, which is scheduled to commence in 2020, should not only greatly improve environmental data on emissions disclosure, but also help set a market price for carbon.

Despite some Chinese companies’ misgivings about being assessed through a Western or developed-market lens, at least by the international ESG ratings agencies, they are becoming more responsive to international investors’ ESG concerns. For example, issuers rated by MSCI ESG have the opportunity to review and comment on their ESG Ratings report and the percentage of covered Chinese companies contacting MSCI doubled between 2017 and 2019.8 CDP, the global disclosure and reporting system for investors, companies, cities, states and regions to manage their environmental impacts, also has seen an increase in Chinese companies reporting on their strategies to manage climate change. There was a 52% increase in companies reporting against the CDP questionnaire from 2016 to 2018.9 We expect this trend to continue as demands from international firms on their Chinese partners’ supply chains, obligations from regulators, a more vocal civil society and investor pressure continue.

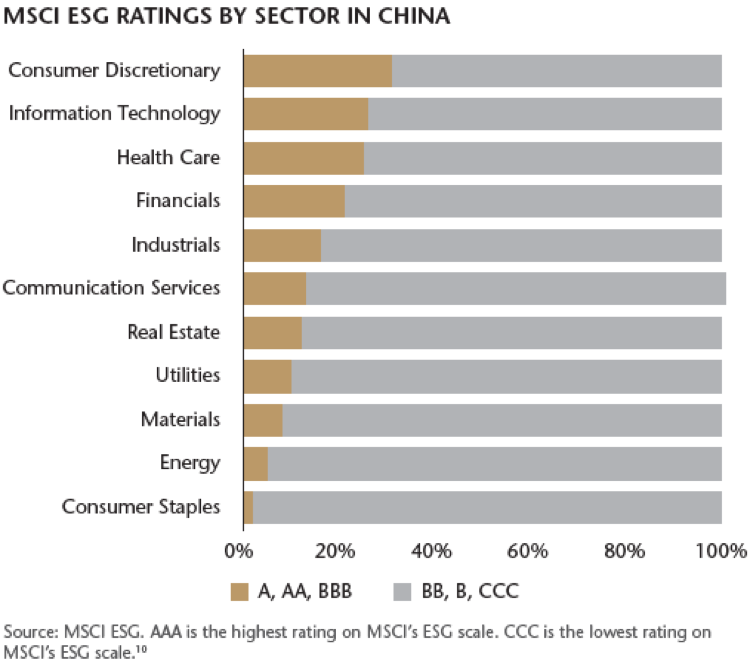

Over recent years, the Chinese economy has transitioned from one with few entrepreneurs to one in which the private sector is the primary engine of GDP, employment and wealth growth. Some of these entrepreneurial firms are listed, and a small share of those have the kinds of business models, corporate governance and interest in shareholder value that make them attractive to us. Finding those firms requires the kind of intensive, on-the-ground due diligence that reflects our investment process. Accordingly, ESG factors represent universally relevant investment criteria, and they are influential in our China investment process, particularly in identifying tail risks. Considering ESG factors tends to be highly compatible with our bottom-up, fundamental investment process, but analysis of ESG inputs must be adapted for the Chinese context. Not surprisingly, some of the sectors we find most attractive are the highest-rated sectors of all companies covered by MSCI ESG Research.

The ESG Data Challenge

While corporate governance practices have improved considerably in China over the past decade, risks remain. Measuring ESG data, including corporate governance metrics, can be challenging. In our opinion, inconsistency in disclosure, definitions and frequency present some of the bigger problems in the data space especially when it comes to measuring very specific key performance indicators. ESG factors tend to have many subjective characteristics and can be difficult to analyze. They may also be difficult to apply consistently across industries or sectors. While strong corporate governance is a good starting point for evaluating individual companies, strong governance on its own is not enough to ensure that a company can generate attractive returns. As active managers, we believe comprehensive due diligence on individual companies is required when pursuing long-term investment objectives.

ACTIVE SECURITY SELECTION IS KEY

In China today, we see strong progress on several fronts in terms of corporate governance practices, although these practices can vary widely from company to company, creating a strong argument in our view for active management. In aggregate, we see progress in greater reporting and transparency on key governance issues. We find a marketplace where majority and minority shareholder interests are increasingly aligned. We also see better capital allocation, at least among the types of higher-quality companies that tend to make it into our investment processes.

We find compelling opportunities in Chinese equities among companies of solid or improving corporate governance. To evaluate corporate-governance quality, we have to go beyond financial statements and ensure interests are aligned between the company and shareholders. We believe that a thorough understanding of the reputation and motivation of people who manage a business is critical when it comes to investing in China. Asset managers cannot conduct this due diligence easily through quantitative screening.

We believe the Chinese market has become more investable, for reasons including improved corporate governance and better disclosures, the ability of companies to create value for investors, company discipline around capital allocation and the fading role of state ownership in certain sectors. New policies and regulations create liabilities for companies, ranging from those using scarce natural resources to those facing potential transition risk and compliance cost burdens. At the same time, cleanup efforts have meant massive demand for environmental technology, innovative solutions and related services.

Our focus always has been on taking a fundamental approach to finding leading Chinese companies that are poised to benefit from the country's structural shift toward its domestic economy, looking beyond the indexes and the headlines. We are encouraged by the trend of China's market liberalization efforts and reform measures. We expect meaningful improvement in each of these areas as ESG-driven and traditional investors alike turn their focus to this expanding market. As China's market evolves to become increasingly driven by company fundamentals, we believe Matthews Asia's long-term, bottom-up investment approach is well-poised to tap into compelling investment opportunities.

1 Sustainable Stock Exchanges Initiative. Data as of November 15, 2019.

2 South China Morning Post, “Securities Commission Backs Introduction of Dual Share Classes,” December 2017

3 HKEX Main Board Listing Rules; Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange Listing Rule; China Securities Regulatory Commission

4 Bloomberg, “China Steps Ups Vigilance on Company Disclosures as Market Opens.” June 2019

5 Reuters, “China Reprimands 130 People During Second Round of Environmental Audits: Xinhua,” August 2019.

6 Ecobusiness.com, “Honest, accurate and transparent? How is China faring at Sustainability Reporting?” August 2019

7 Latham & Watkins, “China Mandates ESG Disclosures for Listed Companies and Bond Issuers,” February 2018

8 MSCI, “China Through an ESG Lens,” September 2019

9 CDP Data Portal, 2016 and 2018

10 MSCI ESG Ratings on 616 Chinese companies as of October 18, 2019. As of October 18, 2019, there were no AAA-rated companies in the MSCI China Index.

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index captures large and mid-cap representation across 23 Emerging Markets (EM) countries. With 833 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float-adjusted market capitalization in each country. Indices are unmanaged and it is not possible to invest directly in an index.

The CSI 300 Index is a capitalization-weighted stock market index designed to replicate the performance of 300 stocks traded in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges. The index, compiled by the China Securities Index Company, Ltd., has been calculated since April 8, 2005.

The China A Index is a free-float weighted equity index, designed to measure performance of China A share securities listed on either the Shanghai or Shenzhen Stock Exchanges. The index was developed with a base value of 1000 as of November 30, 2004.

The MSCI China Index is a free-float weighted equity index. It was developed with a base value of 100 as of December 31, 1992.

Indexes are unmanaged. It is not possible to invest directly in an index.

Investments involve risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investing in international and emerging markets may involve additional risks, such as social and political instability, market illiquidity, exchange-rate fluctuations, a high level of volatility and limited regulation.

Important Information

Matthews Asia is the brand for Matthews International Capital Management, LLC and its direct and indirect subsidiaries.

The information contained herein has been derived from sources believed to be reliable and accurate at the time of compilation, but no representation or warranty (express or implied) is made as to the accuracy or completeness of any of this information. Matthews Asia and its affiliates do not accept any liability for losses either direct or consequential caused by the use of this information. The views and information discussed herein are as of the date of publication, are subject to change and may not reflect current views. The views expressed represent an assessment of market conditions at a specific point in time, are opinions only and should not be relied upon as investment advice regarding a particular investment or markets in general. Such information does not constitute a recommendation to buy or sell specific securities or investment vehicles. This document does not constitute investment advice or an offer to provide investment advisory or investment management services, or the solicitation of an offer to provide investment advisory or investment management services, in any jurisdiction in which an offer or solicitation would be unlawful under the securities law of that jurisdiction. This document may not be reproduced in any form or transmitted to any person without authorization from the issuer.

©2020 Matthews International Capital Management, LLC