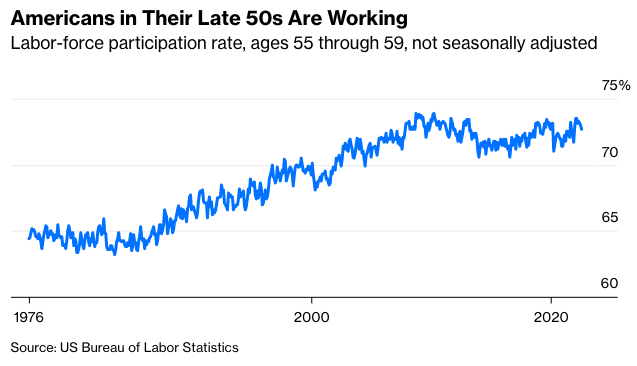

I’m in my late 50s and I’m on the job. So are more than 70% of Americans aged 55 through 59, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In fact, my age group’s labor-force participation rate was approaching record levels earlier this year before undergoing its usual summer decline.

As a result, I tend to bristle a little whenever I read about the big drop in labor-force participation among Americans 55 and older and its supposed adverse effects on the labor market and the economy. It is true that, as of August, the labor-force participation rate for the entire 55-plus age group was, at a seasonally adjusted 38.6%, down 1.7 percentage points from just before the pandemic in February 2020 and near its lowest level in 15 years. But as I’ve already demonstrated, those of us in our late 50s aren’t the problem. We’re still working at record rates!

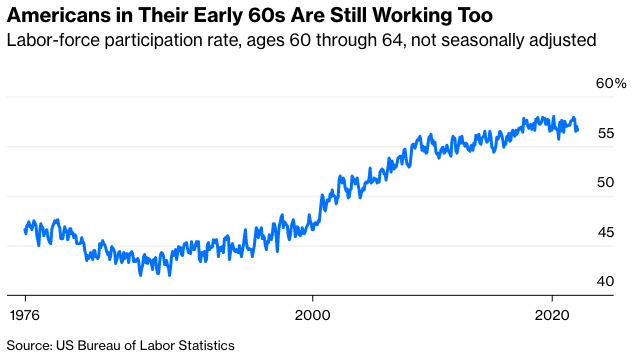

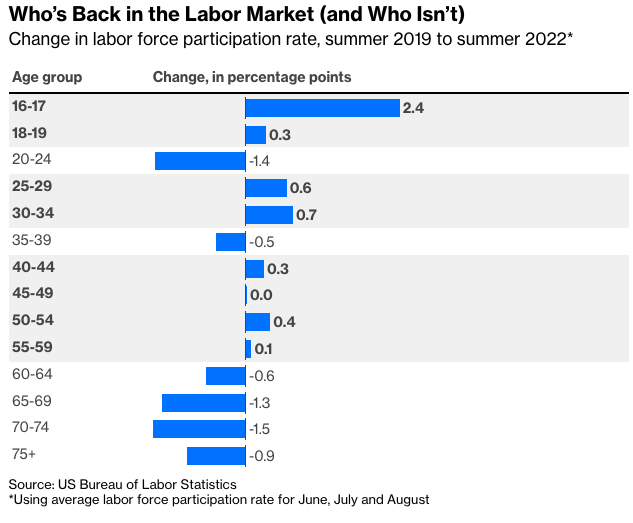

Americans in their early 60s are pretty close to record labor-force participation, too. The big declines are all among those 65 and older. But—and here’s where things get really weird—those declines are still smaller in percentage-point terms than those for the 55-and-older group overall. This strange data quirk is the result of so-called composition effects, caused by the shifting age distribution within the age group, which I’ll discuss a little later. First, though, let’s get around the strange quirk by looking at labor market changes for smaller age groups.

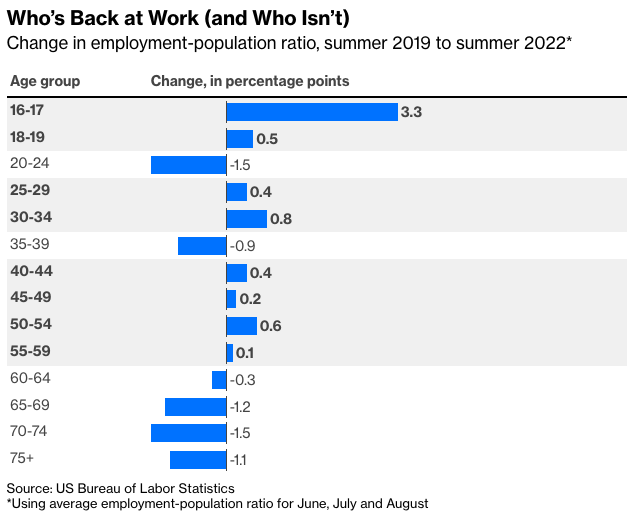

The labor-force participation rate is the estimated number of Americans who have paid jobs (not counting active-duty military) or are looking for work, divided by the civilian, non-institutionalized working-age population. Another key metric, the employment-population ratio, is those with paid jobs divided by population, also excluding active-duty military and the institutionalized. Both are expressed as percentages, so why one is called a rate and the other a ratio is a mystery to me. After this chart I’ll just refer to both as rates.

One thing that stands out here is the apparently limited labor market impact of Long Covid. Lingering effects of Covid-19 are real, and may afflict millions of Americans, but the fact that every under-60 age group but two has higher labor-force participation and employment rates than before the pandemic seems to indicate that Long Covid isn’t keeping significant numbers of working-age Americans out of the workforce.

For workers 60 and older, who in the decades before the pandemic had been experiencing steady gains in labor-force participation and employment, it makes sense that a disease that was far deadlier for the elderly drove many out of the labor force—because of either fear of catching Covid-19 or struggles with Long-Covid complications after catching it. The remarkable performance of stocks and other assets in 2020 and 2021 may also have led some affluent older workers to retire earlier than planned.

The reason the 55-and-older numbers get so much attention is that it’s the one of the few age groups for which the BLS provides seasonally adjusted labor market data. The unadjusted numbers come with big seasonal swings and, especially when you’re looking at narrow age groups such as 55 through 59, a fair amount of month-to-month statistical noise. Still, there are ways to deal with both, such as comparing three-month averages from this summer with those from before the pandemic in 2019.

As for the two under-60 age groups that haven’t returned to or surpassed their summer 2019 participation and employment rates, those in their early 20s may be staying in college longer to make up for pandemic gap years and other delays, or still struggling to recover from the many disruptions to the job market and society in general in 2020. For those in their late 30s child-care complications could be a culprit, although curiously, women in that age group are back to pre-pandemic levels while men are not.

But again, members of the 60-to-64 age group left only briefly. Their labor-force participation rate hit an all-time high in March 2020, when low response rates amid lockdowns may have skewed the data, and came close to that again last November. (“All-time” for these numbers only goes back to June 1976, but statistics available back to 1948 for the broader 55-to-64 age group indicate that recent rates are the highest over that period too.)