Participation among those 60 through 64 was down this summer relative to summer 2019, but that could be evidence of changing seasonal hiring patterns rather than a sustained decline in labor-force attachment. Teenage labor-force participation collapsed in the 2000s, leading traditional teen employers such as McDonald’s to recruit senior citizens for summer jobs. Now hordes of 16-and-17-year-olds are entering the labor force, reducing the need for such efforts.

Those 65 and older have in fact seen a clear drop in labor-force participation after decades of gains. But 65-plussers made up only 6.6% of the labor force in August, compared with the 16.4% share accounted for by those 55 through 64. Their 1.1 percentage point labor-force participation decline since summer 2019 works out to 626,835 missing would-be workers — not nothing, but also not that huge a deal in a labor force of almost 165 million.

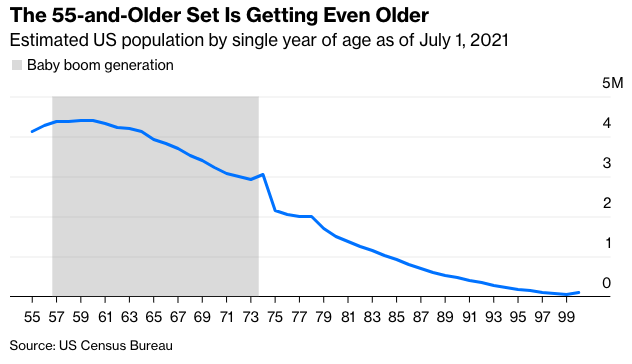

The labor-force participation decline for the broad 55-and-older category is 1.7 percentage points whether measured in seasonally adjusted data from February 2020 or in unadjusted summer-2019-to-summer-2022 comparisons, as I did with the other age groups. How can this be bigger than the decline for those 65 and older, not to mention those in their late 50s and early 60s? Well, the youngest baby boomers are turning 58 this year, meaning that the younger end of the 55-and-older group is now being replenished with the less-numerous members of Generation X.

Because of this, the average age of Americans in the 55 and older category rose even through the ravages of Covid-19 and will continue doing so. (It fell in the Census Bureau’s data from mid-2019 to April 2020 because the 2020 Census found that there were fewer 70-and-older Americans than the bureau had previously estimated, but that's another story.) Meanwhile, labor-force participation tends to peak around age 40, and decline as people age beyond that. So with each passing year, the 55-plus labor-force participation rate will drop even if the rates for every year of age within the group remain the same. The reverse transpired as the baby boomers began to enter the age group two decades ago, as will also be the case for the 75-plus age group that they started joining last year.

The aging of the baby boomers and the U.S. population in general is real and will have a lot of economic consequences, but the seeming mass exodus of 55-and-older workers during the pandemic is to some extent a statistical mirage. That is, many older Americans did leave the workforce, but the irreversible process of aging was as much to blame as the possibly reversible consequences of the pandemic. Those looking to bring more people into the labor market should probably focus on solving the problems that are keeping away would-be workers in their early 20s and late 30s rather than worrying about the oldsters.

Then again, there is another composition effect at work in these statistics that I haven’t discussed. While women’s labor-force participation rates rose from the 1950s through 1990s, men’s fell. So while the current labor-force participation rate for all Americans in their late 50s and early 60s is near an all-time high, for men it’s well below the rates that prevailed before the mid-1970s.

The puzzle of why labor-force participation fell so much among U.S. men of all ages was a major topic of economic discussion in the 2010s that’s probably due for a revival. For those in their late 50s and early 60s the decline wasn’t all bad news, as generous early retirement packages surely drove some of it. Those are less common than they used to be, while boosting male 55-64 labor force participation back to, say, the August 1970 rate of 82.6% would add 2 million would-be workers to the U.S. job market. Bringing the participation rate for so-called prime-age men (25-54) back to 1970 levels would add another 4.5 million. Reversing changes that happened half a century ago is surely a lot harder than reversing those of the past couple of years. But maybe it’s the next frontier.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. A former editorial director of Harvard Business Review, he has written for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is author of The Myth of the Rational Market.