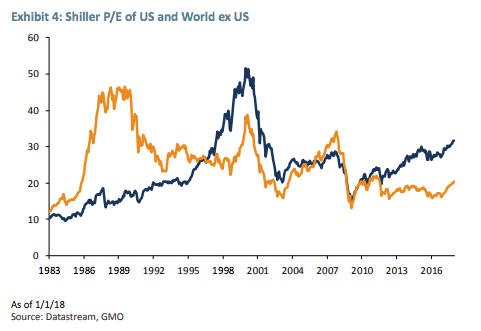

It is possible that the cognitive dissonance of the fully invested bear might not be as puzzling if the U.S. equity market was the only expensive market. That is to say, if the overweight position in equities held by these investors resulted from owning a lot of cheap non-U.S. markets. Indeed, as Exhibit 4 shows, the rest of the world is certainly cheaper than the United States.

But, sadly, saying something is cheaper than the United States is not the same thing as it being cheap in absolute terms. Rather, it is akin to standing next to a pigmy and declaring oneself a giant. So whilst we agree that if you must own equities you should own non-US equities, it is hard to argue that they are not expensive in their own right, which makes it hard for us to want to be overweight equities as an asset class.

The fully invested bear seems to essentially subscribe to Jeremy Grantham’s market melt-up scenario. I certainly can’t rule such an occurrence out. The strongest piece of evidence for it from a personal perspective comes from my own track record of being early in calling bubbles. In 1995, I wrote a piece arguing that Thailand would be the next Mexico (two years too early); in 1997, I wrote piece arguing we were witnessing the last hurrah in equity markets (three years too early); and in 2005, I wrote a piece on the bubble in U.S. housing (two to three years too early). This is the curse of those who follow the edicts of value. Valuation is a useful long-term indicator, but not a good short-term indicator. So perhaps the best way to read my research is to put it in a drawer for two years and then take it out and read it!

Jeremy’s case centers around the fact that many of the psychological hallmarks of the classical bubbles are absent. Effectively, we don’t have the euphoria associated with the great bubble peaks. However, I suspect this is an overly narrow definition of a bubble. In the past I have drawn on a taxonomy of bubbles that seeks to separate out four different kinds of bubbles.4 It should be noted that these bubbles are not always mutually exclusive, and many real-world bubbles exhibit characteristics from more than one type of bubble.

A Taxonomy Of Bubbles

The first and canonical type of bubble is what might be called the “fad” or the “mania.” This is truly a bubble of belief. In this type of bubble, people really do believe that this time is different, that a new era has been begun. These are the great bubbles of history: the TMT bubble, the Japanese bubble, the U.S. housing bubble, and the Roaring 20s all stand out as shining examples of delusional new age thinking.

The second type of bubble is described as an intrinsic bubble. In an intrinsic bubble, it is the fundamentals that are the source of the bubble. That is to say, earnings booming at an unsustainable rate, which then often gives rise to extrapolation and overcapitalization by investors. Financials during the U.S. housing bubble were a good example of this kind of bubble. Their earnings were inflated by the economic bubble in the housing market, and this wasn’t recognized by many investors.

The third type of bubble is known in the academic literature as a near rational bubble. I am not a great fan of this nomenclature as it suggests a veneer of respectability that I find undeserved. To me these are really better described as greater fool markets. They are cynical bubbles in that those buying the asset in question don’t really believe they are buying at fair price (or intrinsic value), but rather are buying because they want to sell to someone else at an even higher price before the bubble bursts. Chuck Prince, the former CEO of Citibank, aptly demonstrated the typical cynical bubble mentality when in July of 2007 he uttered those fateful words, “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We are still dancing.”

I would suggest that this is exactly the sort of market we are observing at the current juncture. Fund managers for the most part all agree that the U.S. market is expensive but still they choose to own equities—a cynical career-risk-driven position if ever there was one. I have been amazed by the number of meetings I’ve had recently where investors have said they simply “have to own U.S. equities.”