Among the many reasons that investors piled into cryptocurrencies this year was the belief that rampant government spending would erode the value of fiat currencies such as the U.S. dollar (hence the quip “have fun staying poor”). Bitcoin, at least in part, was seen as a hedge against inflation.

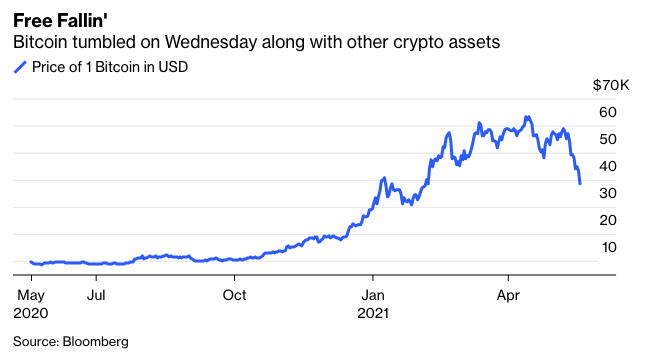

Well, the U.S. certainly got a taste of rapid price growth, with the consumer price index increasing 4.2% in April from a year earlier, the highest since 2008, and the core measure (excluding food and energy) jumping 3%. Inflation, in fact, has become the biggest tail risk in markets. And yet even after that report last week, cryptocurrencies couldn’t seem to find their footing, whether because of tweets from Elon Musk or otherwise. That stumbling turned into an outright freefall on Wednesday, with Bitcoin plunging as much as 30% to about $30,000 while Ether fell more than 40%.

With market and economic pressures flaring, now’s as good a time as any to get reacquainted with an investment that might seem archaic but looks better than most for a way to protect against both inflation and massive spikes in volatility. Call it the anti-Bitcoin: It’s the U.S. Treasury’s Series I savings bonds.

Last September, I wrote that the U.S. government’s Series EE savings bonds seemed like a life hack for fixed-income investing. Recall that the obligations offer an effective yield of 3.5% over two decades, a rate that was almost triple the level of 20-year U.S. Treasuries at the time. Even now, those Treasuries yield barely more than 2%, making the savings bonds look like a bargain. Of course, locking up money for 20 years for that nominal rate is only a good deal if inflation remains in check.

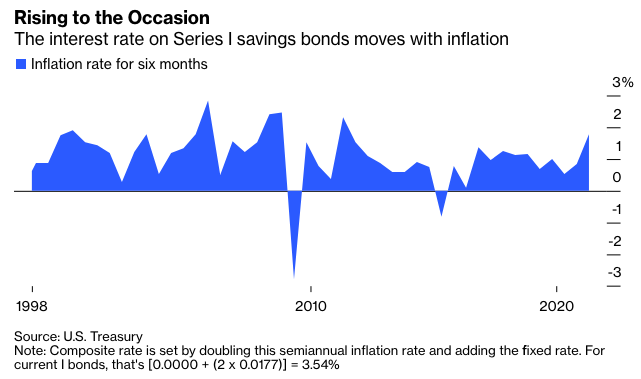

That’s where Series I bonds come into play. The interest rate on these obligations has two components: a fixed rate of return which remains constant and a variable rate set twice a year that rises and falls with headline CPI. From now through October, that composite rate is 3.54%, reflecting a 0% fixed rate and a 1.77% semiannual inflation rate. For some context, that’s higher than the yield on Oracle Corp. bonds due in 2040, Philip Morris International Inc. debt maturing in 2044 and Verizon Communications securities due in 2046, among countless others. It’s not all that far off from the average U.S. junk bond, which yields 4.13%. And it will rise with inflation.

Because savings bonds are non-marketable securities, and there’s a cap of $10,000 per person per year on each series, they typically don’t catch the eyes of traders in the $21.5 trillion Treasury market, nor those involved in crypto, where Bitcoin lost more than $10,000 in the span of hours on Wednesday. (According to TreasuryDirect, in any one calendar year for one Social Security Number, you can buy up to $10,000 in electronic EE bonds, up to $10,000 in electronic I bonds, and, using your tax refund, up to $5,000 in paper I bonds.) But credit to Bloomberg News reporter Joe Light, who brought up the Series I obligations on Twitter last week as a way to protect against inflation. He’s right — for individual investors who believe price growth is here to stay, socking away some cash in I-bonds looks like a no-brainer.

For starters, the nominal interest rate on the securities can never be negative, even if the U.S. were to experience severe deflation. “If the inflation rate is so negative that it would take away more than the fixed rate, we don't let that happen. We stop at zero,” it says on the TreasuryDirect website. That’s a crucial benefit at a time when many sovereign debt yields are still firmly below zero around the world and it sets a lower limit in case views of accelerating inflation turn out to be misguided.

The only slight drawback, aside from the yearly maximum, is the holding period, which can feel stringent in an era when anyone can trade stocks and exchange-traded funds anytime and anywhere from a smartphone. I-bonds must be held for a year, and cashing them in before five years requires forfeiting interest from the previous three months. Otherwise, they have an interest-earning period of 30 years, and, like EE bonds, are exempt from state taxes, plus interest can be excluded from federal income taxes if used to fund education. It’s not a huge tax loophole, to be sure, but executed patiently over many years — say, from the birth of a child through their 18th birthday — it adds up to a tidy sum that won’t be overwhelmed by any level of inflation.

Fed officials have steadfastly argued that current inflation is transitory, caused by material shortages and shipping bottlenecks as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, and they may very well be right. That would argue for policy makers keeping interest rates pinned near zero for years to come. Even in that environment, you could do a lot worse than I-bonds. Savings accounts at major U.S. banks pay practically nothing, and the same goes for money-market funds with the Treasury selling four-week bills at a 0% rate.

I-bonds aren’t going to get anyone rich quick. But as Wednesday’s wild cryptocurrency trading demonstrated, they’re not going to wipe out anyone’s savings in a flash, either. Consider this a reminder that they’re an intriguing option for a bit of tax-efficient inflation protection.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.