With interest-rate cuts off the table for now, the U.S. Federal Reserve will focus on a different topic at next week’s policy-making meeting: when and how to slow quantitative tightening, the process of reducing the vast securities portfolio amassed in previous efforts to support economic activity.

A final plan should be in place by the middle of this year. Whatever happens, the destination matters a lot more than the speed.

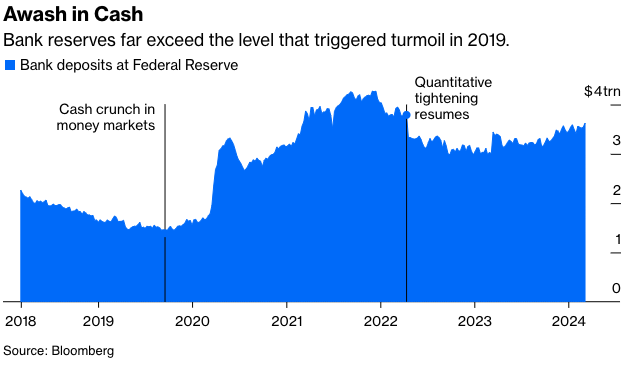

The Fed’s securities holdings affect the amount of cash available in the economy. The central bank’s purchases put money into people’s bank accounts, which the banks then hold in the form of excess reserves. When reserves are abundant, money market rates are stable, underpinned by the interest rate the Fed pays on reserves. When reserves become too scarce—as they did in September 2019—banks scramble for cash and money market rates climb and become volatile.

Problem is, nobody knows exactly at what the level reserves become scarce. Finding it will be like landing a plane with an imprecise altimeter. For this reason, the Fed needs to flatten out its rate of descent as it nears the runway and be extra careful around the point of touchdown.

Right now, there’s still plenty of room for maneuver. Reserves stand at about $3.6 trillion, compared with less than $1.5 trillion in September 2019. Since late 2022, though, they’ve been supported by nearly $2 trillion in outflows from the Fed’s reverse repo facility, set up as a place for non-banks such as money-market mutual funds to park their cash. With only $445 billion remaining in the facility, that supply of reserves will soon end, and reductions in the Fed’s securities holdings will affect reserves more directly.

Hence, the issue of when to slow the pace of quantitative tightening has become more pressing. So far, the Fed has reduced its securities holdings from $8.5 trillion in April 2022 to about $7 trillion today. Its portfolio of Treasury securities is declining at a rate of $60 billion a month. Mortgage securities are shrinking more slowly, by less them $20 billion a month: High interest rates mean people aren’t pre-paying, keeping the runoff rate well below the $35 billion monthly cap.

So what’s the next step? I expect the Fed to reduce the Treasury runoff rate, probably to $30 billion a month. For one, it’s already where the shrinkage has been fastest. Also, the Fed ultimately wants to return to an all-Treasury portfolio. This would avoid the perception that the Fed is allocating credit preferentially to favor the housing sector.

A second issue is which Treasuries to hold. More shorter-term bills would make sense. Their yields move closely in sync with the interest rate paid on banks’ deposits at the Fed, reducing the risk that the central bank’s funding costs will exceed its income. Last year, for example, the Fed lost $110 billion as the cost of paying interest on reserves rose sharply relative to the return on its longer-maturity Treasury and mortgage securities portfolio. And further losses are likely this year. Also, shorter-term holdings would increase the Fed’s capacity to conduct quantitative easing by reinvesting maturing T-bills into longer-term assets rather than expanding its holdings—an attractive option for policy makers concerned about the size of the central bank’s footprint in financial markets.

For all the attention paid to the Fed’s balance-sheet decisions, their effect on longer-term interest rates should be trivial, for various reasons. First, one careful analysis finds that quantitative tightening announcements tend to move rates by no more than 8 basis points–much less than quantitative easing announcements. This is logical given the asymmetry in expectations. Easing requires a big shock to markets or the economy, and hence typically comes as a surprise. Once it’s in place, though, tightening is sure to follow, leaving only the questions of timing, magnitude and duration.

Second, what’s really important is the end point—the level of reserves required to satisfy banks’ demand, avoid market disruptions and ensure that the interest rate on reserves remains the main driver of monetary policy. The abundance created by the Fed’s previous asset purchases has led banks to become more reliant on reserves as a source of liquidity. As a result, I expect the central bank to aim for about $3 trillion, double the level of September 2019.

Finally, decisions on quantitative tightening have no bearing on the timing and magnitude of cuts to the Fed’s short-term interest-rate target. The central bank is shrinking its balance sheet not to tighten monetary policy, but instead to rebuild its capacity for quantitative easing in the future. This will become relevant only if short-term interest rates again reach the zero lower bound or if there is acute Treasury market dysfunction.

Bill Dudley, a Bloomberg Opinion columnist, served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York from 2009 to 2018. He is the chair of the Bretton Woods Committee and has been a nonexecutive director at Swiss bank UBS since 2019.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.