Employment is no doubt the best indicator of the recession I’ve been forecasting. The recent deceleration in U.S. jobs growth suggest that the business downturn may already be underway.

In terms of timeliness, payroll employment is superior among major economic statistics since it is monthly, not quarterly, and reported early, generally on the first Friday of the month for data covering the prior month. This also means that revisions are made relatively soon. And downward revisions are highly important at business cycle peaks.

Government statisticians must weigh the timeliness of economic data against completeness of the samples on which they are based. The surveys of employers’ payrolls are for head counts in the middle of the month, but three weeks later only part of the survey results have been submitted and tabulated. So the initial estimate of payrolls is based in part on the numbers received so far and in part on the trend of previous months. This works fine if payrolls are rising in a steady manner but gives too-high numbers when they’re turning down. So subsequent revisions reduce the original estimate.

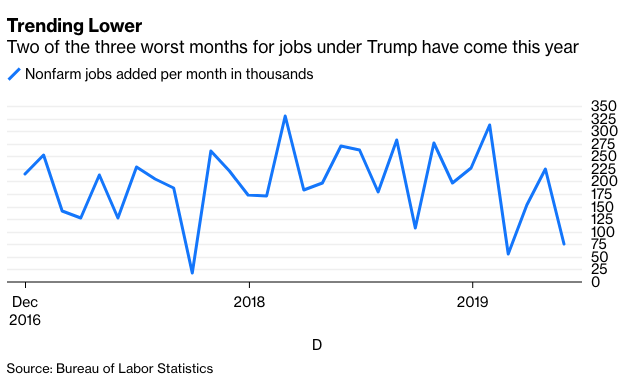

This pattern is clear for monthly payroll data this year. For January, when the job market was still strong, the original estimate was revised from 304,000 to 312,000, and it was revised higher for February as well. But for March, total payroll gains were revised from 196,000 to 153,000 and from 263,000 to 224,000 for April. This suggests that the peak in business activity may have been March and that the low initial increase reported for May of just 75,000 could be cut to a negligible and even negative number upon revision. (The median estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg is that the government on Friday will say 163,000 jobs were created in June.) Hourly wage gains year-over-year slipped from 3.4 percent in February to 3.1 percent in May.

An analysis of post-World War II data reveals that employment often slides from diminishing gains to substantial declines within a few months of the onset of recessions. In December 2007, the initial month of the Great Recession, 110,000 jobs were added but by April they had fallen by 236,000.

The economy, of course, is measured by total spending, and consumer outlays account for 69 percent of total gross domestic product. Since many Americans live paycheck to paycheck, employment weakness soon curbs spending. Also, collapsing job availability scares many consumers into putting a break on expenditures.

Downward revisions in economic data at cyclical peaks tend to be widespread. GDP, the sum of all goods and services produced in the economy in a specific time period, is exactly matched by the gross domestic income generated by that production. It’s paid to employees and individual proprietors along with income from rents and interest as well as corporate profits. But the reported data always has a discrepancy between the two. In the first quarter, real GDP grew at a 3.1 percent annual rate but real GDI advanced only at a 1.4 percent rate. Consequently, the excess of GDP over GDI rose from $23 billion to $99 billion.

Income data, much of it estimated from employment statistics, is less subject to revisions than spending numbers. This rising discrepancy suggests downward revisions in recently-reported GDP numbers are likely. With delays in reporting data and the normal downward revisions, it’s never clear from current information that an economic top has been reached until well into the recession.

The private National Bureau of Economic Research, which did the pioneering work on business cycles back in the 1930s, is the accepted determiner of the dates of peaks and troughs. The NBER’s business-cycle-dating committee wants to be sure of its call so it doesn’t have to backtrack, so it takes some time before declaring cyclical turning points. It was only in December 2008 that the committee announced that the Great Recession had commenced in December 2007, a full 12 months earlier.