Sergio Ermotti is facing a painful reality. For the third time in three years, UBS Group AG’s chief executive officer is resetting his ambitions for the world’s biggest wealth manager. A big fine in France is clouding the outlook for investor returns because it will make payouts uncertain.

The pressure on profit margins is forcing the $2.6 trillion manager to retool its wealth business—and, crucially, to lend more. While the bank will be stung by the dent to its management team’s credibility, it must be careful not to push things too far with the revamp of the unit under Iqbal Khan, a new, energetic wealth manager lured from Credit Suisse Group AG.

Though analysts expected UBS to miss its 2019 earnings targets, the bank still managed to disappoint on Tuesday. At 1.4%, the growth of net new money coming into the wealth manager was well below the firm’s annual target of 2% to 4%. Its cost to income ratio, a measure of efficiency, came in at almost 80%, worse than the 77% target; return on common equity tier 1, the key profitability measure, slipped to 12.4%, well short of the aimed for 15%.

The future’s looking less rosy too. UBS’s new goals shouldn’t be too difficult to achieve, in part because they’re considerably less ambitious than before. Between 2020 and 2022, the return on equity metric should be within 12% to 15%, a range that’s already being hit.

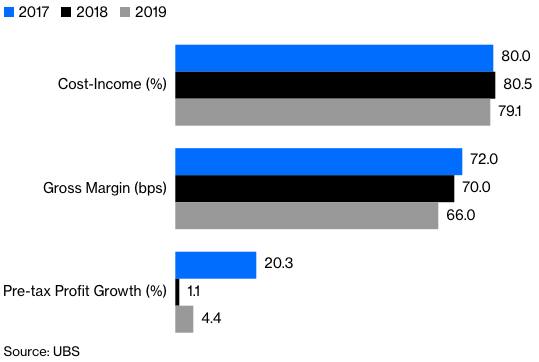

Room For Improvement

UBS's wealth management business has been punching below its weight as margins get squeezed.

The cost to income ratio should improve to 75%-78% and the bank is sticking to pretax profit growth expectations in wealth management of 10%-15% (up from 4.4% in 2019). UBS’s smaller businesses — investment banking, asset management and corporate banking—will no longer have specific growth goals and the bank is abandoning a specific target on net new funds.

While it’s no bad thing to not want to take on more client funds if they just end up sitting in cash and costing UBS because of negative interest rates, the concurrent pursuit of higher profit isn’t exactly worry-free.

Wealth clients are trading more, which should improve transaction income, but the division’s earnings growth will rely heavily on lending and structured products. That may improve margins now, but it’s hard not see UBS taking on greater risks that could backfire later in the economic cycle.

The bank is expanding the collateral it will accept against which to lend money, and loan volumes should increase by about $20 billion a year through 2022. While that’s marginal for a bank with more than $327 billion of loans, a number of single-stock positions backfiring could hit profit.

For Khan, it’s a familiar playbook. More lending (and cost-cutting) helped improve profitability at Credit Suisse; by one measure, income per relationship manager is three times the level at UBS, according to analysts at Citigroup Inc. Khan’s team is eliminating some jobs to streamline the business and speed up decisions, and the bank will cut more costs should the environment deteriorate.

This year, UBS is counting on $1 billion in cost savings already in place to fund investments and to keep group expenses flat. It’s also counting on returns at the UBS investment bank—described by Ermotti as unacceptable in 2019—improving as equity and currency trading shifts to electronic platforms.

There’s not much margin for error. Later this year UBS will appeal against a $5 billion penalty for helping French clients evade taxes. A greater overall focus on cost would reassure investors on the course ahead and ease pressure on bankers from chasing risky lending revenue.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.