Investors, by contrast, are much more sensitive—at least in the short term. It’s happening now: If taxes on the wealthy drop next year, as many tax planners assume they will, then rich people have an incentive to wait until 2018 to recognize investment income by selling stocks or businesses they own. And that seems to be what they’re doing; revenue to the U.S. Treasury dipped this year even as the economy remains strong.

In other words, governments should tax workers more because they can get away with it. However unfair it might be, the disparity doesn’t affect economic behavior as much.

There’s a big flaw, though, in the argument that lower taxes on the rich stimulate longer-term investment, and thus jobs, famously labeled as “trickle-down economics.” While tax rates might affect the timing of some investor decisions in the medium term, it’s much harder to see how they affect long-term behavior. No matter the tax rate, investors ultimately look for opportunities to get richer.

“There is little empirical evidence showing that taxing investors less stimulates savings and growth,” said Emmanuel Saez, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley.

Supply-side economists disagree, and can point to tax cuts in the 1980s that seemed to spur the U.S. and U.K. economies. But there’s little evidence of a relationship between economic growth and investment taxes over the long term.

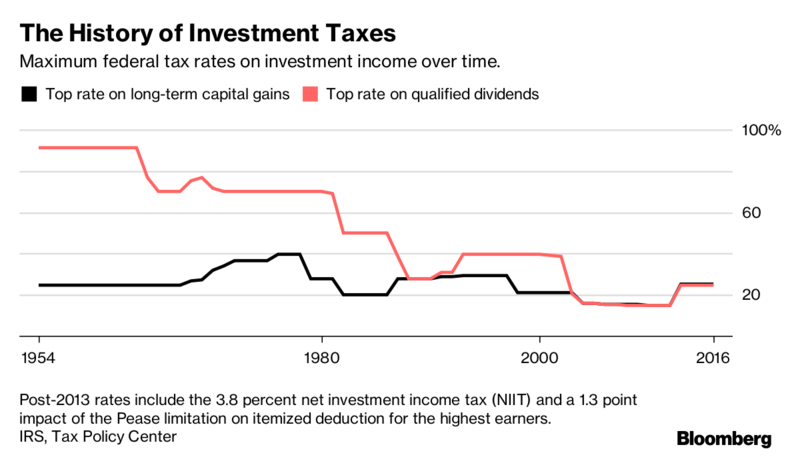

The most famous economic boom in U.S. history, right after World War II, occurred when the top rates on dividends were between 70 and 90 percent. Rapid growth also followed tax hikes on wealthy investors in the late 1980s and early ’90s. And more than a decade later, the Great Recession swamped any conceivable benefits from then-President George W. Bush’s tax cuts, which dropped the top rate on dividends by half.

Democrats, including former President Barack Obama, have proposed higher taxes on investment income. For example, the so-called Buffett Rule would have imposed a minimum rate of 30 percent on all taxpayers with income of $1 million or more, no matter where the money came from. That didn’t pass, but Congress did bump up the rate on capital gains and dividends from 15 percent to 20 percent. And it imposed the net investment income tax, or NIIT, a 3.8 percent levy on wealthy investors, to help fund the Affordable Care Act.

Efforts to kill the NIIT stalled in the Senate along with bids to repeal the ACA, but some House Republicans aren’t giving up. The NIIT is “incredibly anti-growth,” House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady, a Texas Republican, said in July. Last month he acknowledged, however, that getting a repeal bill past the Senate could be “a challenge.” The Tax Foundation, a conservative think tank that relies on its own models, estimates repealing the NIIT would boost the U.S. economy by 0.7 percent over the next 10 years.

Even if you believe low investment taxes can spur economic growth, you might question whether lowering taxes further will have much of an effect these days. The vast majority of wealth held by the middle class is held in homes and retirement accounts. Tapping a retirement account never triggers a capital gains tax, and selling a home only does if the gain is more than $250,000 for a single person and $500,000 for a couple. If you have less than $38,000 in investment income, you already pay a tax rate of zero.

Eliminating the NIIT or lowering other investment taxes is then, at its core, about stimulating the economy by getting the wealthy to save and invest more. But the rich are already saving—a lot. Saez and his Berkeley colleague Gabriel Zucman calculate the top 1 percent of America by wealth have consistently saved more than 30 percent of their income since at least the 1970s.