You spend your days and nights stitching up gunshot wounds and helping children survive asthma attacks. I’ve gotten really good at World of Warcraft, winning EBay auctions, and frying shishito peppers to just the right crispiness.

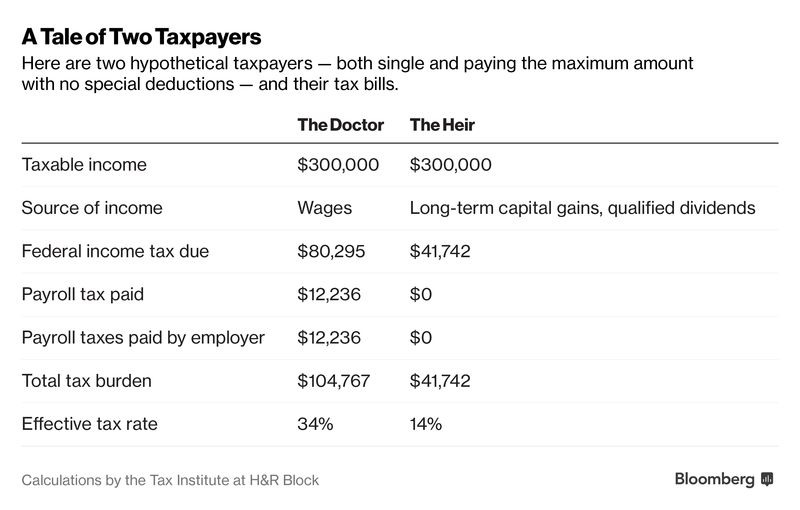

Let’s also say we both report $300,000 in income to the Internal Revenue Service this year. Who pays more in taxes?

You do, by a lot. You owe the IRS about $38,500 more, assuming each of us pays the maximum with no special deductions. I also have more flexibility to lower my burden with tax planning strategies and other tricks, and I get to skip about $24,000 in payroll taxes that you and your employer must fork over each year.

A 1986-style rebalancing is unlikely to happen this fall, however, as President Trump and his fellow Republicans in Congress attempt to tackle tax reform. The gap may even widen further.

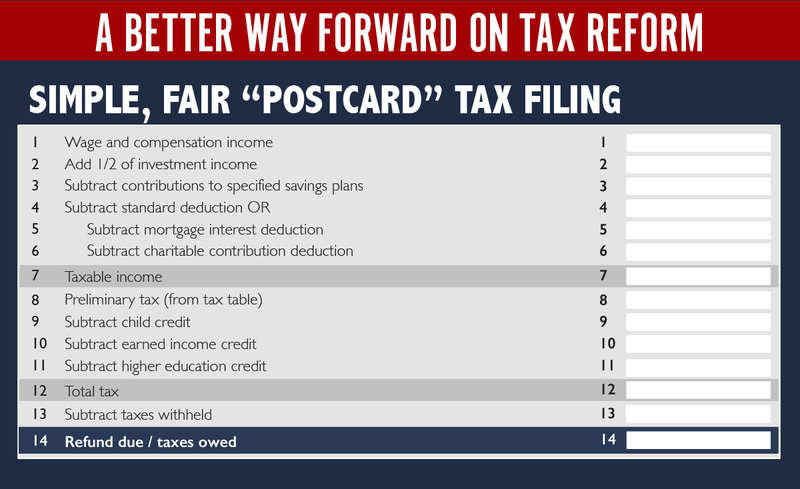

A key goal is to “simplify the [tax] code so much that you can fill out your taxes on a postcard,” House Speaker Paul Ryan said on CNN on Aug. 21. While other details of proposed tax reform remain fuzzy, Ryan and other Republicans have been promoting a draft of that postcard on social media.

The form’s simplicity makes its priorities clear: No matter what rates are applied or which deductions or credits are allowed, a worker would end up paying twice as much in taxes as an investor with the same income. Let’s say you and I are neighbors. You’re an emergency room doctor, and I don’t work, thanks to a pile of money my grandparents left me.

Let’s say you and I are neighbors. You’re an emergency room doctor, and I don’t work, thanks to a pile of money my grandparents left me.

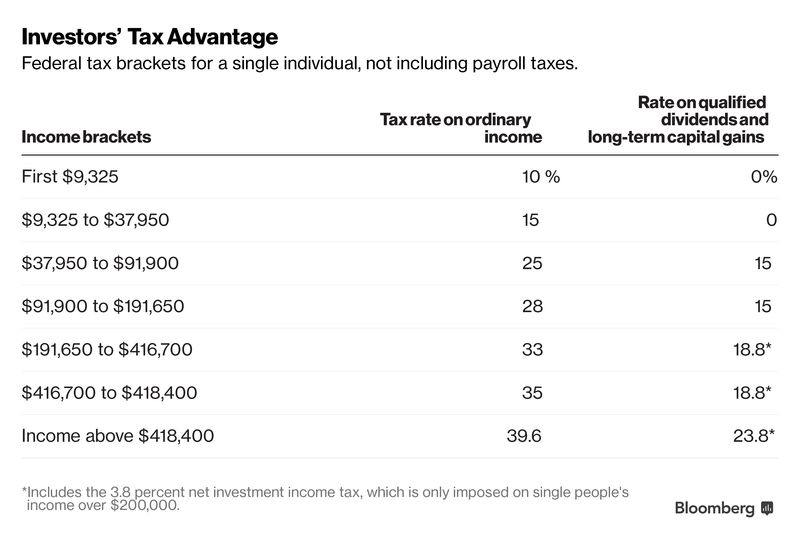

This isn’t some quirk of the U.S. tax code. Politicians have intentionally set tax rates on wages much higher than those on long-term investment returns. The U.S. has a progressive tax system in the sense that well-paid workers sacrifice much more than poor workers on their “ordinary income.” But Americans with so-called unearned income—qualified dividends and long-term capital gains—get a break. A billionaire investor can pay about the same marginal rate as a $40,000-a-year worker, a fact Warren Buffett has famously lamented.

The last time Congress passed comprehensive tax reform, in 1986, it eliminated the gap between workers’ and investors’ taxes. Their rates didn’t start diverging again until the early ’90s, when Congresses controlled by Democrats boosted taxes on wealthy Americans’ wages more than on their investments. Republican-controlled Congresses widened the gap further by slashing rates on rich investors in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The first line asks filers to write down their previous year’s wages. For you—the ER doctor in the fictional scenario above—that would be $300,000. The second line asks filers to add just half of their investment income. For me, that would be $150,000.

Why American Workers Pay Twice As Much In Taxes As Wealthy Investors

September 12, 2017

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment