It should be no surprise that Bitcoin sold for over $44,000 this week, more than double its March 13 price. Going back to 2014, it has taken the cryptocurrency an average of nine months and 21 days to double; the milestone came 28 days early this time.

What is mildly surprising is that Bitcoin doubled without ever falling below its March 13 low. On average, it has dropped 27% between doublings (that is, if it starts from $1,000, it drops to $730 before trading above $2,000) and it has dropped as much as 83% (trading for $170 before going to $2,000).

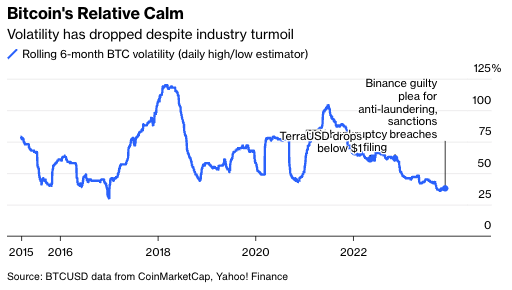

Even that is mostly old news as volatility has steadily declined since a Covid-era peak. Annualized volatility has been 50% over the last two years, no higher than many large technology stocks. Moreover, this relative calm has occurred over a period with massive scandals, bankruptcies, prosecutions and regulatory fights in crypto.

Does this mean Bitcoin can be invited to the grown-up table at this year’s holiday dinner, to have its own place in standard portfolios?

For most investors the answer is still “no.” Bitcoin has more than enough appreciation potential to attract investors, and its volatility no longer seems to be a disqualification. Issues like secure custody, tax treatment and legality seem mostly solved. But its correlations with other major assets—particularly stocks, currencies and gold—have been unstable, making it hard to fit in, like a left-handed dinner guest.

Back in 2011, I estimated crypto would be 3% of the global economy. As an efficient market investor, I have since kept 3% of my net worth in crypto when volatility was low and when it was high, and when crypto was soaring and crashing. But most investors prefer investments that behave in at least semi-predictable ways to fundamental events and prefer buy-and-hold to constantly responding to price changes. (Disclosure: I also have venture capital investments and advisory relations with crypto companies.)

The original value case for Bitcoin was as a transaction currency. It was far more efficient than the traditional financial system for international transfers, the unbanked and citizens of financially repressive regimes.

Bitcoin also proved convenient for rarely prosecuted crimes like recreational drug sales, prostitution and gambling. Despite a popular myth, it is not a good currency for serious criminal activity such as terrorism or murder-for-hire, because transactions are public and immutable. It’s true they are also pseudonymous—you don’t have to use your real name—but investigators have little trouble tracing individuals via patterns of flows. Serious criminals do better with government-issued cash, assets like gold or diamonds, or privacy-protected cryptocurrencies like Monero or ZCash.

At this week’s Senate Banking Committee hearings, Senator Elizabeth Warren agreed with JPMorgan Chase & Co. CEO Jamie Dimon and other bankers that anti-money-laundering controls should be applied to crypto. While laws can make it difficult to move traditional currencies in or out of crypto for criminal purposes, there is no way to prevent or track direct transfers within privacy-protected crypto, and financial repression to combat money laundering is one of the things that drives people—both honest and dishonest—to use crypto.