Baltussen put this in numeric terms, saying the team had found “outperformances of 3.9% in periods of yield rises and 3.0% in periods of yield declines.” In other words, factor performance tends to persist also when yields increase. So it looks as though they’ve found a way to improve on the market returns on bonds, year in and year out.

All of this looks a little bit too good to be true, which is never a good sign. Why should factors have this strong and enduring an effect on buying and selling of bonds? Baltussen suggests that it shouldn’t be that surprising. The factors all come ultimately from flaws in human nature, which is a constant. The momentum effect, for example, is based in our behavior and our tendency to overreact, and it is visible in equities, commodities and currencies. Bond markets are strongly driven by sentiment around central banks and core macroeconomic indicators. But then we have seen over the past week that emotion on these matters is prone to overshooting and exaggeration, even if the tendency isn’t as egregious as it can be in hot stocks.

Another complaint common to the burgeoning production line for such research in equities is that many of the factors identified by academics are abstruse and over-defined to fit limited data sets. In this case, government bonds are a reasonably well defined universe, and the data set is big, but there are bound to be questions over numbers that go so far back in history.

In any back test, we are also looking at a factor that nobody had identified and tried to exploit. If people buying and selling bonds issued to finance the Napoleonic wars or the U.S. war of independence had had access to this research, then it is conceivable that these anomalies would have been eliminated earlier. Much more conceivably, the effects could start to go away if bond investors start systematic factor-investing in a big way, and the idea gets marketed to ETF-issuers and pension funds.

In areas like this, the disciplines of academic research can probably do the job. Other academics will pummel the data, and we will see whether it is really this easy to exploit anomalies in the bond market. Meanwhile, the research is practical as well as fascinating, and it is a fair bet that ETFs will be aiming to use it before long.

Building A Bridge

How big a deal is it, then, that there might just be a bipartisan deal to spend almost $600 billion on infrastructure — meaning mostly the most basic physical assets, like roads, bridges and tunnels? Even if this looks like quite an achievement for President Biden (as there just aren’t the votes in Congress for a truly liberal wish-list of spending), it had little obvious direct impact on bond markets. U.S. stocks have had a good few days, with the S&P 500 back at an all-time record. The infrastructure narrative probably helped a bit, just as the earlier political difficulties weighed on the market.

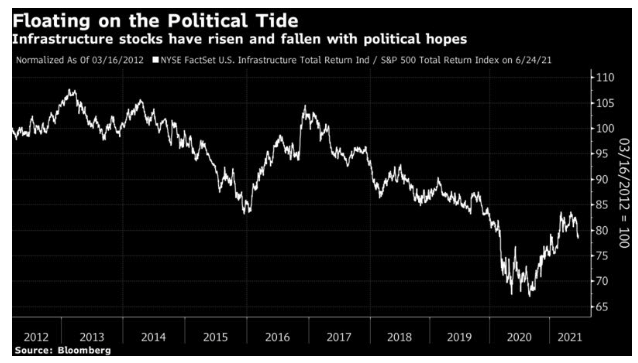

In terms of direct impact, this deal should certainly improve the fortunes of infrastructure groups, many of which are concentrated in energy. The NYSE Factset U.S. Infrastructure index has tended to rise and fall with its political prospects over the last decade, which has meant that it has generally dropped compared to the market:

President Bill Clinton won the last truly dull and predictable U.S. presidential election, in 1996, with the forgettable slogan that he was “building a bridge to the 21st century.” Whatever else happened subsequently in Clinton’s eventful second term, this particular pledge went seriously unfulfilled, at least in a literal sense. The American record of undertaking big infrastructure projects in the quarter-century since 1996 has been terrible. Presidents of both parties have tried and failed to get some bridge-building done amid widespread indifference.

Smart Beta Has Worked For Bonds Since Napoleon

June 25, 2021

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment