This scarcely sounded like a propitious time to buy. So how might someone have decided to invest?

Arguably, the key point was that the radical uncertainty caused by the pandemic had created great risk of a financial crisis. The bond market appeared to be broken. An all-out failure of payment systems, with a liquidity failure to be followed swiftly by a solvency crisis, was a very real possibility. That was why central bankers tried so desperately to fix the problem.

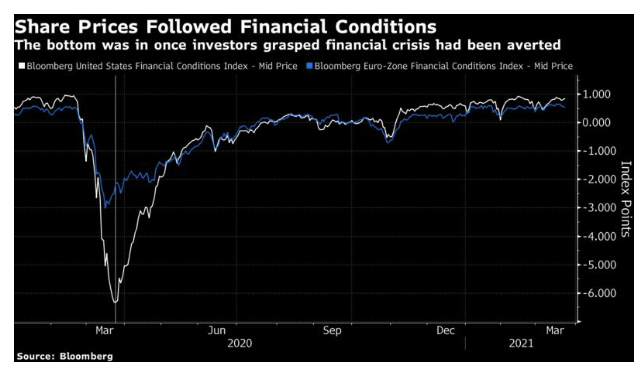

If we look at Bloomberg’s financial conditions indexes, which incorporate a number of different measures, we see that financial conditions in the EU had begun to improve a week earlier, while in the U.S. they had stopped falling on the Monday before the rebound started. With hindsight, we can see that the bottom was in. The risk of an all-out financial crisis soon receded, and stock gains over the ensuing months were boosted by the steady decline in the chances of a solvency or bankruptcy event. The pandemic was a difficult risk to measure, but the possibility of a financial crisis was much easier to gauge, and investors had clarity that it was receding. That was one way to decide to buy stocks.

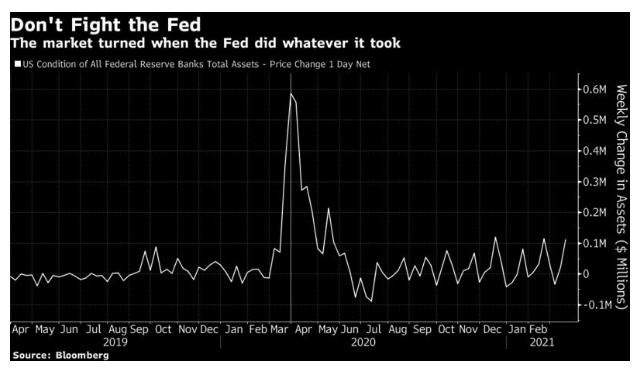

Put only slightly differently, the way to buy at the bottom was to follow the old market cliche and not fight the Fed. The package of measures that Jerome Powell outlined that Sunday night was a bazooka. Nobody could fight it. Indeed, Jim Bianco was probably right to say that they had virtually nationalized the bond market. If we go by weekly changes in the Fed’s balance sheet, there was a clear sign that the time to stop selling had arrived. The vertical line again shows the week of the turnaround:

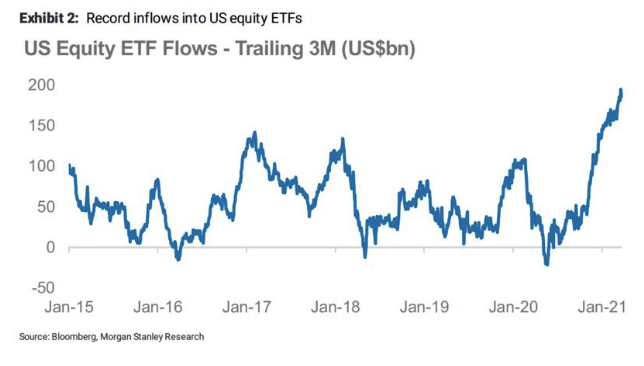

Beyond the Fed’s buying, there was also liquidity from normal investors who don’t have the power to create their own money. Flows into U.S. equity ETFs turned around in the week of the rally’s beginning, and then surfed onward for 12 months. Following liquidity and its creation clearly helped ensure that this rally turned into one for the ages:

Accountability Time

So, did Points of Return (i.e., me) help you to spot this historic buying opportunity in real time? Not really. But there were some pieces of the puzzle in there.

On the Monday after the Fed fired its bazooka, this column offered a “crisis map for investors.” James Bullard of the St Louis Fed had suggested that the U.S. unemployment rate could hit 30%, a number too terrible to contemplate. This suggested that revulsion was at hand: