Writing in 1982, White wasn’t concerned with hyperinflation, as seen in the Weimar Republic or Zimbabwe. U.S. inflation had peaked in 1980 just above 14%. Yet his work sounds similar to much prose written over the last decade about the evils of inequality, long-term unemployment, the gig economy, and deaths of despair. He was writing angrily about a condition that had become an intolerable part of life, and also with no grasp that it had already peaked. By the end of 1982, the year he published, it had dropped all the way to 3.8%. Paul Volcker had been appointed to chair the Fed by Carter in 1978, and was in the process of winning the war on inflation—but amazingly, a great journalist could write about inflation in 1982 without ever once mentioning his name.

White gets across that inflation appeared inevitable and unavoidable. By the summer of 1979, he says, “no other issue could rival the inflation as a pressure on the American mind.” Conversation before the 1980 election was “stained and drenched in money talk, by what it cost to live or what it cost to enjoy life.” White talks about how inflation had come to divide the nation, and how all politicians shared a desperate aim to beat it. Reagan’s campaign had many themes:

But underlying them all was the appeal to the Untermensch of politics: The government is cheating you, inflation is stealing away from you the value of your dollars.

Four decades later, with the Fed established as by far the most important institution in the global economy, people talk in exactly the same kind of apocalyptic terms about how lack of inflation leaves us being cheated by a thieving government. Four decades from now, it’s easy to imagine that historians will think it obvious that the current deflationary regime had become intolerable, and that it was already being shifted.

How To Change A Regime

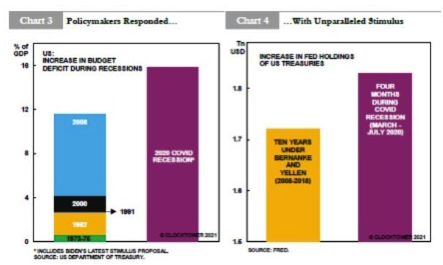

Inflation psychology is difficult to change. But last year might do the job. The monetary and fiscal response was of a different order of magnitude from the crises that preceded it. The following chart is from Marko Papic of Clocktower Group:

Meanwhile, the Fed’s intent is clear. Chairman Jerome Powell stresses the urgency of dealing with unemployment and the inequities it causes. The following comments are quoted by Dylan Grice of Calderwood Capital in his Popular Delusions newsletter:

“The big picture is still that we’ve seen … three decades, a quarter of a century, of lower and more stable inflation and we’ve seen really the last decade be characterized by global disinflationary forces and large advanced economy nations struggling to reach their 2% inflation goal from below...

We have had inflation dynamics in our economy for three decades which consists of a very flat Philips curve, meaning a weak relationship between high resource utilization, low unemployment and inflation, but also low persistence of inflation, critically … of course those dynamics will evolve, but its hard to make the case why they will evolve very suddenly, in this current situation.

I described our new framework and our guidance, in major part we are looking at actual inflation, we want to see actual inflation, and part of the reason for that is that all during the long expansion, many of us—and that includes me—were writing down a return to 2% inflation, and maybe a mild overshoot, year after year after year. And year after year after year, inflation fell short of that. So we have tied ourselves to realizing actual inflation.”

“Volcker said he was going to tame inflation, unemployment be damned,” says Alex Lennard of Ruffer LLP. “Now it’s the other way around. I don’t think people have quite realized that you’ve had this huge change in the mandate of policymakers.”

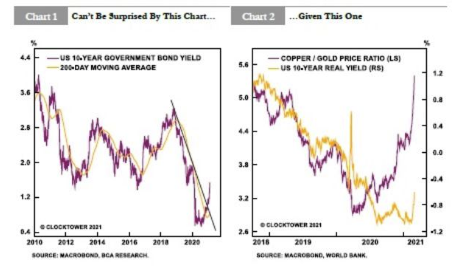

Added to this, there is now an agreement on fiscal expansion. Politicians around the world appear to be “going big.” Meanwhile, as Papic of Clocktower shows, the underlying market moves have been suggesting a change in direction for a while:

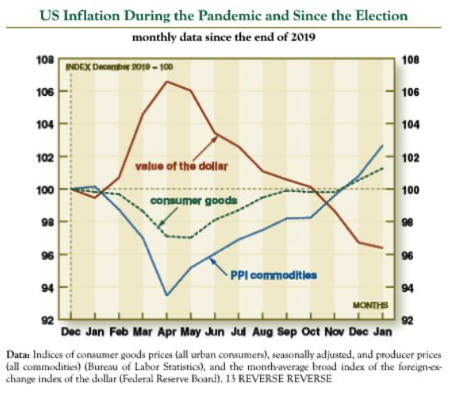

As for the constituent parts of inflation, this chart from David Ranson of HC Wainwright & Co. demonstrates a clear turn last year, which in the U.S. has been accelerated by the weakening of the dollar—a phenomenon that is widely expected to continue:

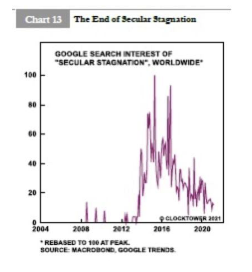

At a more subtle level, while concern about inequality and the hollowing out of the middle class occupies politicians across the spectrum, worries about “secular stagnation” have quietly disappeared: