It may also be observed that the initial withdrawal rate decreases with the severity of inflation.

10/1/1929 retiree: 5.5% initial withdrawal rate (30-year average inflation rate = 1.9%)

10/1/1936 retiree: 5.3% initial withdrawal rate (30-year average inflation rate = 2.9%)

10/1/1968 retiree: 4.5% initial withdrawal rate (30-year average inflation rate = 5.3%)

I coined the term “SAFEMAX” to denote the lowest initial withdrawal rate in my database, which for almost 50 years has been 4.5% and is associated with the 1968 retiree. In the foregoing analysis, we have in effect identified three different “SAFEMAX” percentages for three different inflationary regimes. This provides the opportunity to recommend an initial withdrawal rate higher than 4.5% if there is confidence that the current inflationary regime is more benign than it was in the 1970s.

Each of these three portfolios experienced one or more bear markets early in the investor’s retirement, which appears to be a necessary condition for a low initial withdrawal rate. This is the noted “sequence-of-returns” phenomenon.

Although much emphasis in past studies (including my own) has been placed on the sequence of returns to account for the sustainability of a portfolio, our new discussion demonstrates that considerable weight should also be given to the sequence of inflation. Given that inflation has been quiescent for most of the last quarter century, it may have dropped off of some advisors’ radar screens

It is no accident that the “worst worst case” scenario (with the lowest initial withdrawal rate) was faced by the 1968 investor, who experienced the highest inflation surge of the last 90 years. In contrast, the 1929 investor experienced a far deeper drawdown in stock prices, but early deflation produced an initial withdrawal rate more than 20% higher.

Like sequence-of-returns, high inflation relatively early in retirement is critical. That’s because, in my methods, dollar withdrawals are increased each year by the prior year’s inflation rates. This tends to “lock in” elevated dollar withdrawals for the remainder of retirement. In contrast, stocks and portfolio values often recover from short-term declines, even if they are large in magnitude.

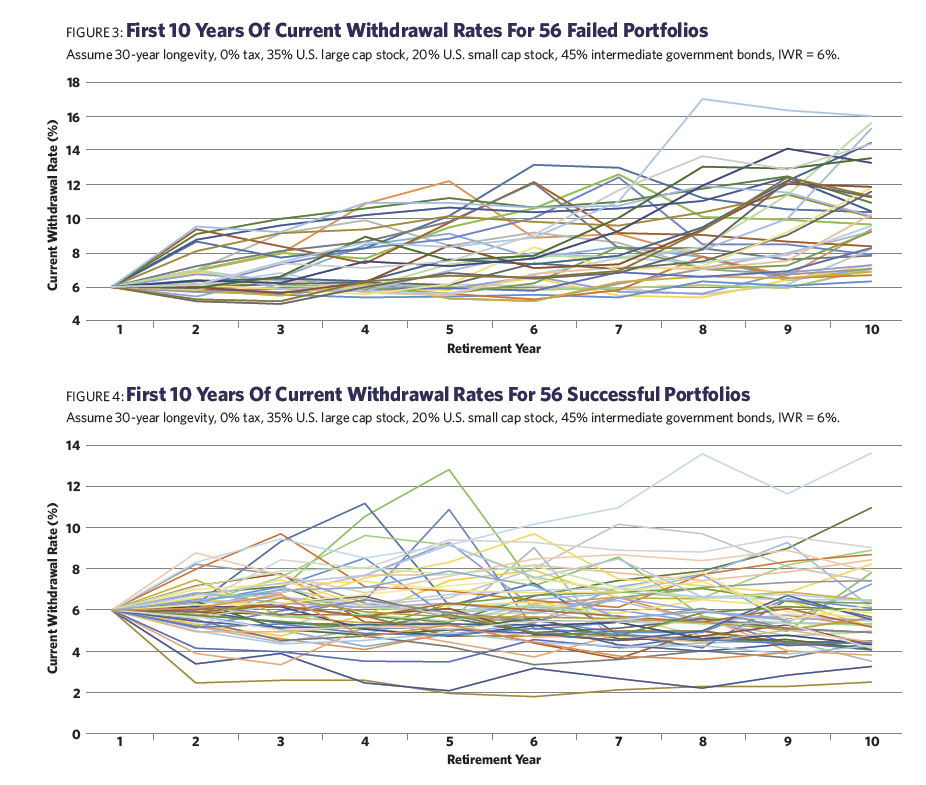

I like the current withdrawal rate as a measure of portfolio stability because it incorporates information from the two critical components of portfolio health: the value of the portfolio (reflecting input, or portfolio returns) and the dollar withdrawals from the portfolio (representing output). Portfolio values alone are an inadequate indicator, as low investment returns may be offset by slow growth (or even decline) in dollar withdrawals. This begs a question: Is the current withdrawal rate by itself sufficient to recognize a failing withdrawal plan?