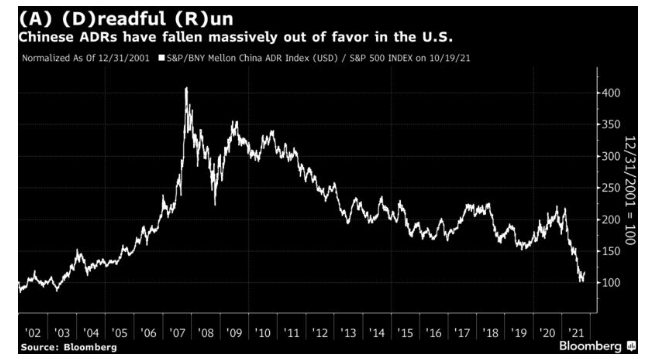

The succession of increasingly anti-capitalist moves by the Xi administration had clear negative impacts on stocks in China, but few had any great impact back in the States. However, if we look at the performance of Chinese American depositary receipts, or ADRs, covering larger companies, the way they have fallen from grace in the last few months is dramatic. Being based in China is plainly now seen as a disadvantage, after years of being viewed as a benefit for which investors would pay for a premium:

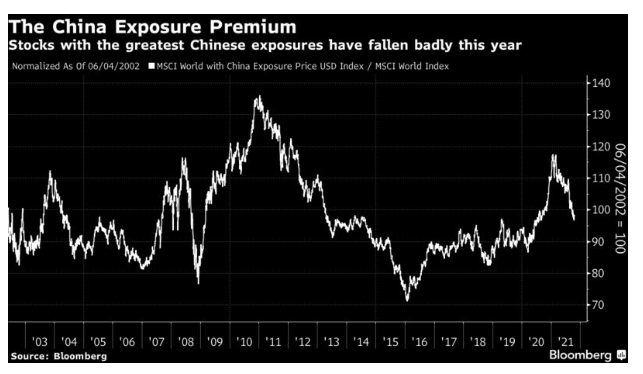

The performance of the 50 stocks within the MSCI World index with the greatest exposure to mainland China yields a similar result. Economic exposure to the country went even further out of favor around the 2015 devaluation, but this year’s fall has been dramatic. It’s hard to explain it as anything other than a response to the political clampdown. China’s governance and political risks now look much higher:

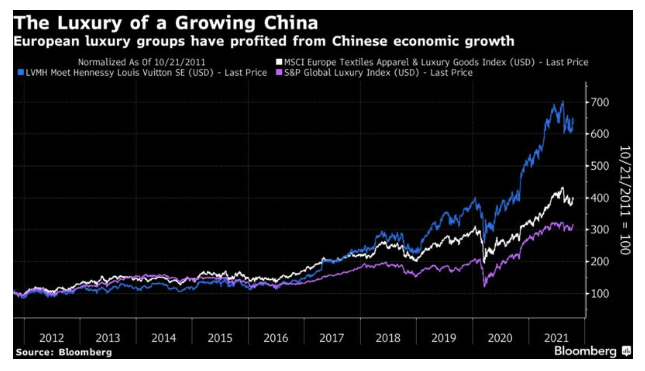

If there is any single sector that stands to be affected, it is luxury goods makers. Paced by the extraordinary success of LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE, luxury goods makers have had a great few years:

A Chinese slowdown might slow demand for luxury goods. If that’s the case, these companies could have much further to fall.

How great are Chinese political risks? For more than a generation now, the country has continued to call itself communist while being unabashedly pragmatic, and allowing the profit motive to help achieve many aims. Rothman of Matthews Asia, a former U.S. diplomat in the country and a long-time bull on Chinese assets, makes the case that political risks are now overstated in his blog, which you can find here. He reads Xi’s “common prosperity" program as an attempt to avoid the polarization and inequality that have come to plague the West, rather than a return to ham-fisted Leninism. His main point is that China has come far too far on the back of entrepreneurship to turn back now:

This perspective is based on the uncertainties caused by the rapid and chaotic roll out of new regulations, rather than on the long-term objectives announced by leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Market-based reforms and the private sector have created the economic growth which has kept the CCP in power for far longer than most other one-party, authoritarian regimes. Reversing these reforms would destroy China’s economy, which would destroy popular support for the CCP. Why would Party leaders take what would clearly be a politically suicidal path?

There is sense to this, and China’s political risks look to have been well priced. But for the time being it will be difficult to spark much investment into China itself. The risk that isn’t yet priced, and looks harder to avoid, is that slowing Chinese growth will have negative effects in the West.