The Labor Market

The other factor raising inflation fears is the labor market. The non-farm payroll data, published last week, include figures on the rise in average hourly and weekly earnings. Despite the disappointing rise in payrolls, the data showed earnings continuing to rise healthily. In itself, this is a positive development that may yet alleviate much social tension. But it also implies inflationary pressure.

There are two problems with the data. One is the compositional effect. The most poorly paid workers tended to be laid off during the Covid shutdown last spring, with the result that the average earnings of those left shot up. A second issue concerns base effects. Comparing to 12 months ago risks a false comparison with an extreme low.

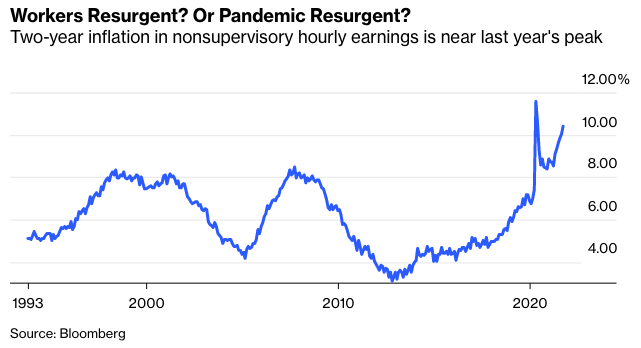

To try to deal with this very simply, I put together the following chart, which takes the two-year inflation rate (since September 2019, before the pandemic even started) of the average earnings for people in nonsupervisory positions. These will tend to be lower-paid workers. This is how the two-year increase in their pay has moved since 1993:

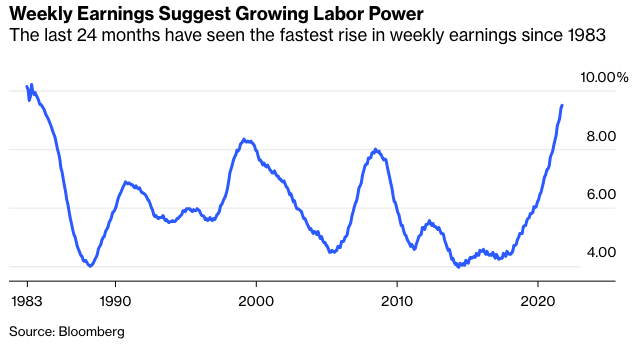

There are also data for weekly earnings, which can help spot when employers are keeping pay constant but cutting employees’ hours. This tends to be seasonal, so in the following chart, I’ve looked at the 24-month moving average of two-year inflation of average weekly earnings. The data go back to 1983, and since that year, on this basis, U.S. wage inflation has never been as high as it is now:

Many caveats apply. There may still be compositional effects distorting the numbers. The pandemic is still impacting the behavior of employers and employees alike. And more granular data (such as the wage tracker data due from the Atlanta Fed in the next few days) should give a much more accurate picture. Also, note that the levels of wage inflation showing up at present are not at all excessive, and only look high in comparison to a long period in which labor has had a very raw deal.

But at the margin, it is completely reasonable for numbers like this to awaken fears that inflation will be higher than the forecasts had been projecting.

The Corporate Sector

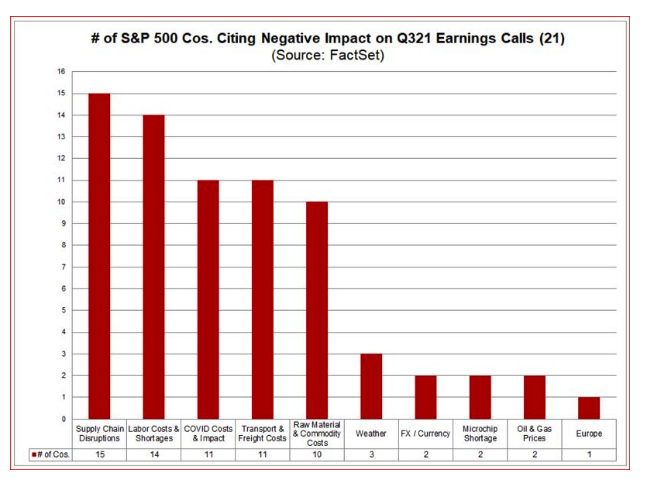

The earnings season for the third quarter is about to get underway, and it will inevitably provide much anecdotal information on how businesses are dealing with prices. Judging by the few companies to have reported already, many will take the opportunity to warn about supply shortages and rising prices. It’s possible that they will be doing this to excuse poor performance; after all, it’s a CEO’s job to put as good a gloss as possible on the results. But these numbers for the 21 S&P 500 companies to have reported so far, produced by John Butters of Factset, do show that bottlenecks and inflation are dominating discussion, and they are doing so more than a year after the worst shutdown conditions were lifted: