Let’s take a look at these arguments one by one.

The 10-year average real EPS, the denominator of the CAPE ratio, changes over time. Siegel argues that in periods of high growth, the 10-year average real EPS is biased downward because recent higher earnings are underrepresented; the result is that CAPE is artificially pushed higher. Siegel (2016) shows that real EPS growth from 1871 to 1945 was a scant 0.68 percent a year, then skyrocketed in the post-war period to 3.07 percent, but the real return on stocks remained essentially unchanged. Both pre- and post-war rates are compound annual growth rates, depending entirely on their starting and ending levels. Why did Siegel choose 1945, a year of deeply depressed earnings as the end point for his “slow-growth” early years and starting point for his “fast-growth” post-war years? Trend growth rates, which are far less sensitive to start and end dates, differed much less dramatically at 0.8 percent pre-war and 1.8 percent post-war.

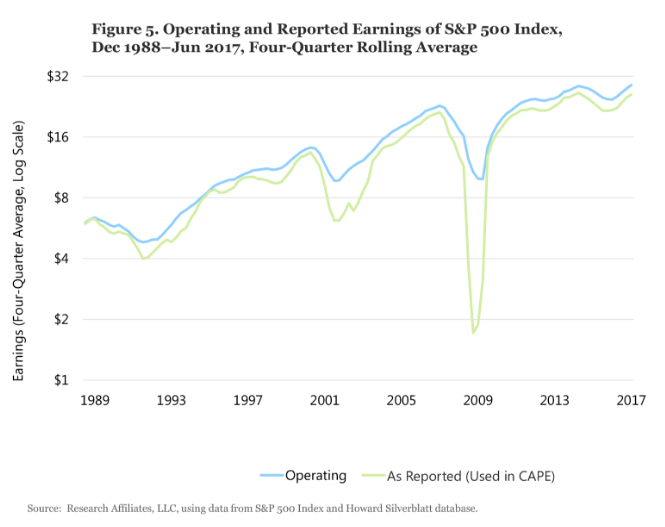

Siegel also argues that changes to accounting rules over the last two decades, specifically from FAS Nos. 115, 142, and 144, require companies to write down assets for a variety of reasons, such as impairment of goodwill or to fair market value for securities “available for sale.” The result is that the CAPE denominator is biased downward relative to history when calculated using generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP, earnings. Companies, however, can bypass these write downs by reporting non-GAAP operating earnings and have increasingly taken the liberty of doing so. Figure 5 clearly illustrates that the operating earnings versus GAAP “gap” that was reliable, but modest, in the 1980s and 1990s has in subsequent years become much larger.

Even if we embrace the use of operating earnings in computing CAPE, it makes comparatively little difference to the outcome when we make the same adjustment to the historical CAPE averages. Although operating and reported earnings can vary dramatically from quarter to quarter, operating earnings have been, on average, 10 percent higher than reported earnings. The historical norm against which the adjusted CAPE should be compared would also be lower. Tower (2013) has done important work showing that when we embrace Siegel’s many proposed “fixes” for the CAPE, and recompute the historical average CAPE to reflect the changed method, the relative CAPE “signal” changes surprisingly little.