Finally, as an alternative earnings measure, Siegel argues for the use of the Bureau of Economic Analysis national income and product accounts (NIPA) measure of profits as a long-term data series that can be used without interruption, because it is unaffected by the aforementioned changes in accounting rules. We disagree. NIPA profits includes all US companies, and makes no adjustments for the cost of starting new businesses or taking companies private. The natural dilution associated with entrepreneurial capitalism (IPOs and secondary equity offerings) reduces shareholders’ ownership interest in existing public companies—it’s as if we can get these new stock offerings for free. Also, because NIPA profits includes all companies, public and private, it gets an added boost from the fact that the publicly traded share of the economy is shrinking—it’s as if we can pocket the proceeds of privatization and still own the profits of a fast-growing roster of businesses that are being taken private. Finally, NIPA profits is not a globally available measure, limiting our ability to use it to compare international markets, an important feature for investors using financial ratios to determine their desired allocations to these markets.

Changes In The Discount Rate

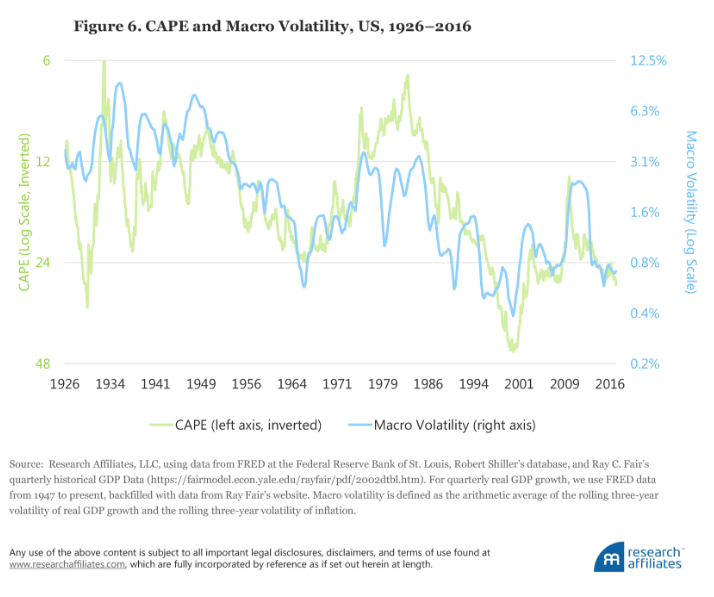

Recently, our colleagues Aked, Mazzoleni, and Shakernia (2017) looked at discount rates from a top-down macro perspective and found the fair-value multiple for equities is time varying and negatively related to changes in macroeconomic risk. The proxies for these risks are rolling three-year volatility in real GDP growth and in inflation. Their thesis is that a secular decline in macroeconomic risk over the past few decades has made investors more comfortable with holding risk assets at lower discount rates (higher PE multiples). They find, assuming the current low level of macro volatility, that an equilibrium CAPE of 23, which is nearly 30 percent below the current level of 32, can be justified. As Figure 6 shows, over the past two decades, macro volatility has been low and is currently well under 1 percent. For equilibrium CAPE to remain at 23, macro volatility must remain at its current low level.

Macro volatility is, unsurprisingly, related to equity market volatility, and recent low macro volatility has helped US equity market volatility hit a near-record low. The drop was significant enough for some to suggest we now live in an era characterized by low volatility. Ironically, similar talking points of sustained new eras of low volatility were common in 1999 and 2007. We all remember what followed. And now US Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen is claiming she does not believe we will experience another financial crisis in our lifetimes (Reuters, 2017). We may not see a repeat of 2000–2002 or 2008–2009, but when volatility—whether macroeconomic or equity—hits a historical low, it is more likely to move higher than to continue its march toward zero.